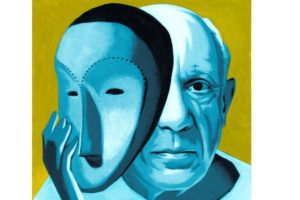

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

The lemonade stand has symbolized American childhood and values for more than a century. Norman Rockwell even created a classic 1950s drawing of children getting their first taste of capitalism with the help of a little sugar and lemon. Yet like apple pie, the lemonade stand is far older than America itself.

The lemon’s origins remain uncertain. A related fruit with far less juice, the citron, slowly migrated west until it reached Rome in the first few centuries A.D. Citrons were prestige items for the rich, prized for their smell, supposed medicinal virtues and ability to keep away moths. Emperor Nero supposedly ate citrons not because he liked the taste but because he believed that they offered protection against poisoning. Continue reading…