When today’s travelers get in trouble for knocking over statues or defacing temples, they’re following an obnoxious tradition that dates back to the Romans.

September 8, 2023

Tourists are giving tourism a bad name. The industry is a vital cog in the world economy, generating more than 10% of global GDP in 2019. But the antisocial behavior of a significant minority is causing some popular destinations to enact new rules and limits. Among the list of egregious tourist incidents this year, two drunk Americans had to be rescued off the Eiffel Tower, a group of Germans in Italy knocked over a 150-year-old statue while taking selfies, and a Canadian teen in Japan defaced an 8th-century temple.

It’s ironic that sightseeing, one of the great perks of civilization, has become one of its downsides. The ancient Greeks called it theoria and considered it to be both good for the mind and essential for appreciating one’s own culture. As the 5th-century B.C. Greek poet Lysippus quipped: “If you’ve never seen Athens, your brain’s a morass./If you’ve seen it and weren’t entranced, you’re an ass.”

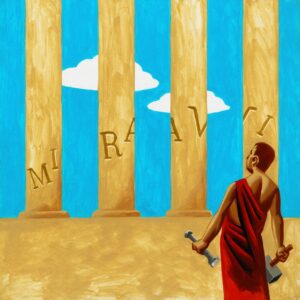

The Romans surpassed the Greeks in their love of travel. Unfortunately, they became the prototype for that tourist cliché, the “ugly American,” since they were rich, entitled and careless of other people’s heritage. The Romans never saw an ancient monument they didn’t want to buy, steal or cover in graffiti. The word “miravi”—“I was amazed”—was the Latin equivalent of “Kilroy was here,” and can be found all over Egypt and the Mediterranean.

Thomas Fuchs

Mass tourism picked up during the Middle Ages, facilitated by the Crusades and the popularity of religious pilgrimages. But so did the Roman habit of treating every ancient building like a public visitor’s book. The French Crusader Lord de Coucy actually painted his family coat of arms onto one of the columns of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

In 17th- and 18th-century Europe, the scions of aristocratic families would embark on a Grand Tour of famous sights, especially in France and Italy. The idea was to turn them into sophisticated men of the world, but for many young men, the real point of the jaunt was to sample bordellos and be drunk and disorderly without fear of their parents finding out.

Even after the Grand Tour went out of fashion, the figure of the tourist usually conjured up negative images. Visiting Alexandria in Egypt in the 19th century, the French novelist Gustave Flaubert raged at the “imbecile” who had painted the words “Thompson of Sunderland” in six-foot-high letters on Pompey’s Pillar in Alexandria in Egypt. The perpetrators were in fact the rescued crew of a ship named the Thompson.

Flaubert was nevertheless right about the sheer destructiveness of some tourists. Souvenir hunters were among the worst offenders. In the Victorian era, Stonehenge in England was chipped and chiseled with such careless disregard that one of its massive stones eventually collapsed.

Sometimes tourists go beyond vandalism to outright madness. Jerusalem Syndrome, first recognized in the Middle Ages, is the sudden onset of religious delusions while visiting the biblical city. Stendhal Syndrome is an acute psychosomatic reaction to the beauty of Florence’s artworks, named for the French writer who suffered such an attack in 1817. There’s also Paris Syndrome, a transient psychosis triggered by extreme feelings of letdown on encountering the real Paris.

As for Stockholm Syndrome, when an abused person identifies with their abuser, there’s little chance of it developing in any of the places held hostage by hordes of tourists.

‘If sack [wine] and sugar be a fault, God help the wicked,” says the rollicking Sir John Falstaff in Shakespeare’s “Henry IV, Part 1.” That was a more innocent time. Nowadays, books such as Gary Taubes’s “The Case Against Sugar” have linked it to many of the world’s health crises, including diabetes, obesity and high blood pressure.

‘If sack [wine] and sugar be a fault, God help the wicked,” says the rollicking Sir John Falstaff in Shakespeare’s “Henry IV, Part 1.” That was a more innocent time. Nowadays, books such as Gary Taubes’s “The Case Against Sugar” have linked it to many of the world’s health crises, including diabetes, obesity and high blood pressure.