A Note on Eighteenth Century Politics by Amanda Foreman

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, lived during a period of rapid change. The population was sharply increasing, the national income was rising, roads were improving, and literacy was spreading. Britain was on the verge of becoming a great power, driven by its burgeoning factories at home and fertile territories abroad. But with fewer than ten million people, the country was still small enough to be governed by an aristocratic oligarchy.

There were roughly two hundred peers (as British aristocrats are called) when Georgiana married the Duke of Devonshire. There were only twenty-eight dukes, but because of their wealth and rank they exerted a disproportionate influence in politics. As a duchess, Georgiana was one tier below royalty; below her the titles descended in the order of marquess and marchioness, earl and countess, viscount and viscountess, and lord and lady. The peers sat by right of birth in the House of Lords, the upper chamber of the Houses of Parliament. The only form of retirement for a peer was death. Indeed, in 1778 the Earl of Chatham made a dramatic exit from the floor of the Lords, dying of a heart attack in mid-speech.

While the two hundred or so peers sat in isolated splendour in the Lords, their sons, cousins, brothers-in-law, friends, and hangers-on filled up the House of Commons, the lower chamber in Parliament. Britain was a democracy in the sense that every five years a general election took place and voters elected 558 members of Parliament, known as MPs, to sit in the Commons. However, property restrictions kept the number of voters small—roughly three hundred thousand, or 3 percent of the population. There were all kinds of legal anomalies and customs which enabled peers and gentlemen of sufficient wealth to actually own a seat outright, or have so much influence in the constituency, that democracy did not enter into the equation at all. The peerage spent a great deal of money and effort trying to control as many seats in the Commons as possible. But aristocratic patronage never extended to more than two hundred MPs, leaving the majority open to some form of contest.

There was enough popular participation to make politics as big a national obsession as sport, if not bigger. The emergence of national newspapers turned politicians into celebrities. The talk in coffee houses and inns up and down the country was on the quality of the speeches the day before, on who had acquitted himself in the finest manner and whether the government—meaning the monarchy—had won the argument. For the aristocracy, politics was not just a sport but a business. It dominated their lives, destroying some in the process and elevating others to even greater wealth and glory.

Although women did not have the vote, were barred from the House of Commons, and could not hold an official position, Georgiana was a passionate contestant in the political arena. She devoted herself to the Whig party: campaigning, scheming, fund-raising, and recruiting for it right up until the day she died. The story of her extraordinary life is a mirror of the past; look into it and you will see the turbulent history of late-eighteenth-century politics unfold.

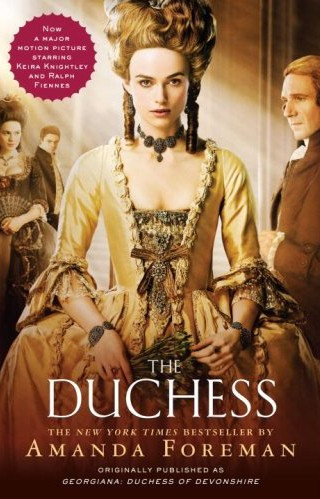

Purchase the Book from Barnes & Noble