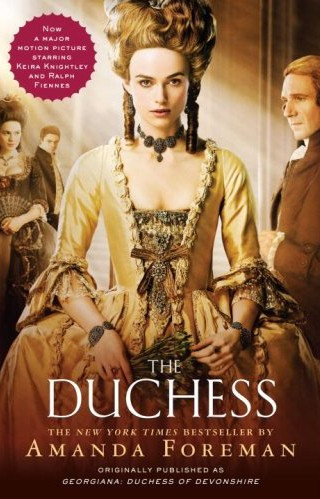

Extract from the USA book The Duchess by Amanda Foreman

C H A P T E R 1

DÉBUTANTE

1757–1774

I know I was handsome . . . and have always been fashionable, but I do assure you,” Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, wrote to her daughter at the end of her life, “our negligence and ommissions have been forgiven and we have been loved, more from our being free from airs than from any other circumstance.”* Lacking airs was only part of her charm. She had always fascinated people. According to the retired French diplomat Louis Dutens, who wrote a memoir of English society in the 1780s and 1790s, “When she appeared, every eye was turned towards her; when absent, she was the subject of universal conversation.” Georgiana was not classically pretty, but she was tall, arresting, sexually attractive, and extremely stylish. Indeed, the newspapers dubbed her the Empress of Fashion.

The famous Gainsborough portrait of Georgiana succeeds in capturing something of the enigmatic charm which her contemporaries found so compelling. However, it is not an accurate depiction of her features: her eyes were heavier, her mouth larger. Georgiana’s son Hart (short for Marquess of Hartington) insisted that no artist ever succeeded in painting a true representation of his mother. Her character was too full of contradictions, the spirit which animated her thoughts too quick to be caught in a single expression.

Georgiana Spencer was the eldest child of the Earl and Countess Spencer.* She was born on June 7, 1757, at the family country seat, Althorp Park, situated some one hundred miles north of London in the sheep-farming county of Northamptonshire. She was a precocious and affectionate baby and the birth of her brother George, a year later, failed to diminish Lady Spencer’s infatuation with her daughter. Georgiana would always have first place in her heart, she confessed: “I will own I feel so partial to my Dear little Gee, that I think I never shall love another so well.” The arrival of a second daughter, Harriet, in 1761 did not alter Lady Spencer’s feelings. Writing soon after the birth, she dismissed Georgiana’s sister as a “little ugly girl” with “no beauty to brag of but an abundance of fine brown hair.” The special bond between Georgiana and her mother endured throughout her childhood and beyond. They loved each other with a rare intensity. “You are my best and dearest friend,” Georgiana told her when she was seventeen. “You have my heart and may do what you will with it.”

By contrast, Georgiana—like her sister and brother—was always a little frightened of her father. He was not violent, but his explosive temper inspired awe and sometimes terror. “I believe he was a man of generous and amiable disposition,” wrote his grandson, who never knew him. But his character had been spoiled, partly by almost continual ill-health and partly by his “having been placed at too early a period of his life in the possession of what then appeared to him inexhaustible wealth.” Georgiana’s father was only eleven when his own father died of alcoholism, leaving behind an estate worth £750,000—roughly equivalent to $74 million today.† It was one of the largest fortunes in England and included 100,000 acres in twenty-seven different counties, five substantial residences, and a sumptuous collection of plate, jewels, and old-master paintings. Lord Spencer had an income of £700 a week in an era when a gentleman could live off £300 a year.

Georgiana’s earliest memories were of travelling between the five houses. She learnt to associate the change in seasons with her family’s move to a different location. During the “season,” when society took up residence “in town” and Parliament was in session, they lived in a draughty, old-fashioned house in Grosvenor Street a few minutes’ walk from where the American embassy now resides. In the summer, when the stench of the cesspool next to the house and the clouds of dust generated by passing traffic became unbearable, they took refuge at Wimbledon Park, a Palladian villa on the outskirts of London. In the autumn they went north to their hunting lodge in Pytchley outside Kettering, and in the winter months, from November to March, they stayed at Althorp, the country seat of the Spencers for over three hundred years.

When the diarist John Evelyn visited Althorp in the seventeenth century he described the H-shaped building as almost palatial, “a noble pile . . . such as may become a great prince.” He particularly admired the great saloon, which had been the courtyard of the house until one of Georgiana’s ancestors covered it over with a glass roof. To Lord and Lady Spencer it was the ballroom; to the children it was an indoor playground. On rainy days they would take turns to slide down the famous ten-foot-wide staircase or run around the first-floor gallery playing tag. From the top of the stairs, dominating the hall, a full-length portrait of Robert, first Baron Spencer (created 1603), gazed down at his descendants, whose lesser portraits lined the ground floor.*

* Misspellings have been corrected only where they intrude on the text.

* Georgiana became Lady Georgiana Spencer at the age of eight when her father, John Spencer, was created the first Earl Spencer in 1765. For the purpose of continuity the Spencers will be referred to as Lord and Lady throughout.

† The usual method for estimating equivalent twentieth-century dollar values is to multiply by 100.

* The Spencers originally came from Warwickshire, where they farmed sheep. They were successful businessmen, and with each generation the family grew a little richer. By 1508 John Spencer had saved enough capital to purchase the 300-acre estate of Althorp. He also acquired a coat of arms and a knighthood from Henry VIII. His descendants were no less diligent, and a hundred years later, when Robert Spencer was having his portrait painted for the saloon, he was at the head of one of the richest farming families in England. King James I, who could never resist an attractive young man, gave him a peerage and a diplomatic post to the court of Duke Frederick of Württemberg. From then on the Spencers left farming to their agents and concentrated on court politics.