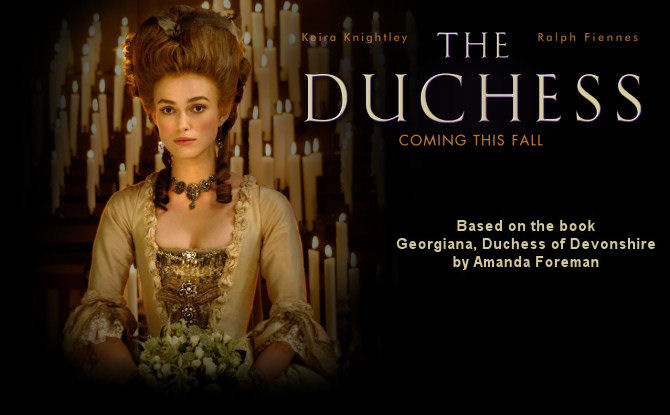

Excerpts from the Book Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire: Coming to Society

Extract from the book Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire by Amanda Foreman

Situated opposite what is now the Ritz Hotel, Devonshire House commanded magnificent views over Green Park. The original house had burnt down in 1733 and the third Duke of Devonshire commissioned William Kent to rebuild it. Aesthetically it was a failure. The house was stark and devoid of architectural detail; the bottom windows were too large, the top windows too small. The whole building was enclosed behind a brick wall which hid the ground floor from view and made the street unattractive to passers-by. The London topographer, James Ralph, wrote, ‘It is spacious, and so are the East India Company’s warehouses; and both are equally deserving of praise.’ As well as attracting every graffiti writer within two miles, the brick wall ruined the architectural line of Piccadilly. One contemporary complained: ‘The Duke of Devonshire’s is one of those which present a horrid blank of wall, cheerless and unsociable by day, and terrible by night. Would it be credible that any man of taste, fashion, and figure would prefer the solitary grandeur of enclosing himself in a jail, to the enjoyment of the first view in Britain, which he might possess by throwing down this execrable brick screen?’

The chief attraction of Devonshire House was the public rooms, which were larger and more ornate than almost anything to be seen in London. A crown of 1,200 could easily sweep through the house during a ball, a remarkable contrast to some great houses where the crush could lift a person off his feet and carry him from room to room. Guests entered the house by an outer staircase which took them directly to the first floor. Inside was a hall two storeys high – flanked on either side by two drawing rooms, several anterooms and the dining rom. Some of the finest paintings in England adorned the walls, including Rembrandt’s Old Man in Turkish Dress, and Poussin’s et in Arcadia Ego.

Georgiana and the Duke were naturally placed to become leaders of society’s most select group, known as the ton or ‘the World’ – the ultra-fashionable people who decided whether a play was a success, an artist a genius, or what colour would be ‘in’ that season. Henry Fielding was only half-joking when he said that ‘Nobody’ was ‘all the people in Great Britain, except about 1200’. The ton certainly believed this to be the case. The writer and reluctant courtier Fanny Burney made fun of its self-absorption in Cecilia: ‘Why, he’s the very head of the ton,’ Miss Larolles says of Mr. Matthews. ‘There’s nothing in the world so fashionable as taking no notice of things, and never seeing people, and saying nothing at all, and never hearing a word, and not knowing one’s own acquaintance, and always finding fault; all the ton do so.’

The social tyrants who made up the ton also considered it deeply unfashionable for a wife and husband to be seen too much in each other’s company. The Duke escorted Georgiana to the opera once and then resumed his habit of visiting Brooks’s, where he always ordered the same supper – a broiled blad-bone of muitton – and played cards until five or six in the morning. Occasionally they went to a party together but Georgiana was expected to make her own social arrangements. There was no shortage or invitations and she accepted everything – routs, assemblies, card parties, promenades in the park – in an effort to avoid sitting alone in Devonshire House.

With her instinctive ability to make an impression, Georgiana immediately caused a sensation. She always appeared natural, even when she was called upon to open a ball in front of 800 people. She could engage in friendly chatter with several people simultaneously, leaving each with the impression that it had been a memorable event. She was ‘so handsome, so agreeable, so obliging in her manner, that I amquite in love with her,’ Mrs Delaney burbled to a friend. ‘I can’t tell you all the civil things she said, and really they deserve a better name, which is kindness embellished by politeness. I hope she will illumine and reform her contemporaries!’ Even cynics like Horace Walpole found their resistance worn down by Georgiana’s unforced charm and directness. Observing her transformation into a society figure, Walpole marvelled that this ‘lovely girl, natural, and full of grace’ could retain these qualities and yet be so much on show. ‘The Duchess of Devonshire effaces all,’ he wrote a few weeks after her arrival in London. She achieved it ‘without being a beauty; but her youth, figure, flowing good nature, sense and lively modesty, and modest familiarity, make her a phenonemon’.