How do you solve a problem like Georgiana?

I did not know anything in my twenties. I don’t mean I was stupid or ignorant. I simply knew nothing of the world. My contemporaries were climbing the job ladder and buying houses. I, on the other hand, was reading about a tiny little area, within a small field, of a narrow aspect of 18th-century British history.

The area in question was the life of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, 1757-1806, known in her lifetime as the Empress of Fashion and the doyenne of the Whig party. Until I began my research, my acquaintance with her had been limited to the few lines she garnered in general histories of the period. She had campaigned for the Whig party during the general election of 1784, allegedly trading kisses for votes; and, long before he became prime minister, Earl Grey was her lover.

Neither of those pieces of information had led me to believe she merited further investigation. In fact, I was already deep into a different dissertation when, by good fortune, I picked up a biography of Earl Grey that quoted several of her letters. I was smitten by the end of the first.

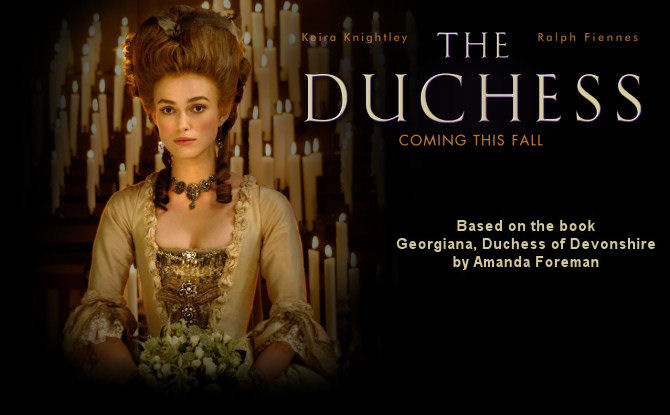

I devoted the next five years to her. Undistracted by a social life or the needs of a family, I simultaneously wrote a doctoral thesis and a commercial biography. The book, called Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, became an international bestseller, the subject of a docudrama for Channel 4, a radio play for Radio 4 starring Judi Dench, and, now, a film, The Duchess, starring Keira Knightley as Georgiana, and Ralph Fiennes as her husband, the 5th Duke of Devonshire.

Georgiana wrote to her correspondents as if she were speaking directly to them. She had, in contrast to every other human being I have ever encountered, no filter to her thoughts. When I say that I was smitten, I mean she captivated me to the point where my desire to release her voice into the present became an obsession. She dazzled and fascinated me. She seemed to be everything I wasn’t: a wife, a mother, a leader of society and a very public figure. Even her problems were more interesting than mine.

When I wrote about the 27-year-old Georgiana campaigning in the infamous 1784 election, I was exactly the same age. She had already been married for 10 years. She was fully formed — or, at least, I thought so — whereas I had come to her as raw and as unmade as it is possible for a biographer to be. Yet I knew at the time of writing that something profound connected us. I didn’t realise what it was, however, until 13 years later, when I watched Knightley during the filming of The Duchess. Then it struck me with the force of a blunt instrument. We had shared a set of assumptions — a framework of beliefs — that are the essence of youth. I maintained those beliefs while writing the book, even as Georgiana’s changed. Yet at the time, I was too young and inexperienced to notice. From start to finish, in my mind’s eye Georgiana was always the 27-year-old heroine fighting to be the agent of her own destiny. As I look at her now, I see someone quite different.

When Georgiana married the Duke of Devonshire at the age of 16, her sole desire was to please him and not to be an embarrassment in front of his friends. As the eldest daughter of the 1st Earl Spencer, she had been brought up to make a good match. But nothing in her education prepared Georgiana for her sudden fame. The duke’s vast wealth and political power as the financial patron of the Whig party placed Georgiana on a tall, lonely pedestal. In the beginning, every day brought new hurdles, and therefore new terrors, to be faced. However, by the end of Georgiana’s first year of married life, she had become the darling of 18th-century society. She combined an extraordinary talent for making people feel special with an uncanny ability to be the centre of attention.

Georgiana’s youth was a handicap at first, but, as the film cleverly shows, it protected her when she started to experiment with her clothes. Society likes fresh young talent with bold ideas. Georgiana was not only unafraid to challenge the rules of fashion, she relished the opportunity to exert her power. As Knightley’s Georgiana explains to Fiennes’s duke in the film: “You have so many ways of expressing yourself, whereas we must make do with our hats and dresses.” She turned each public entrance into a moment of drama. “When she appeared, every eye was turned towards her,” wrote the French ambassador — and a character declares in The Duchess: “When absent, she was the subject of universal conversation.”

Georgiana’s unprecedented social success was accompanied by untrammelled private excess. Gambling was all the rage in the late 18th century. For Georgiana, though, it was an addiction. She ran up debts so large that a true reckoning would have bankrupted the Devonshire estate several times over. She took drugs to block out her emotions. She binged and purged like a modern-day bulimic. At least some of her many miscarriages can be traced to her extraordinarily destructive lifestyle.

Addiction, as we now know, is a disease, but Georgiana might not have become a gambling addict if she had been married to a supportive husband or benefited from an understanding mother. Unfortunately, the duke was the only man in England who was unmoved by his wife. Shy and emotionally inarticulate, he ought to have married a self-confident, mature woman whose sole aim in life was to make him happy. Instead, he chose a needy adolescent whose clinginess repulsed him. Yet when she sought public adulation as a compensation, he felt wounded and bitter.

The Devonshires had been married for eight childless years when Lady Elizabeth Foster, “Bess”, descended upon them. Georgiana was at the height of her social prowess, having made her role as the premier Whig hostess into much more than a matter of political dinners and handshakes on election day. Yet the gnawing loneliness remained. “When I first came into the world, the novelty of the scene made me like everything,” she admitted to a friend. “However, now my heart feels only an emptiness in the beau monde which cannot be filled.”

The wily, calculating Bess, played by Hayley Atwell in The Duchess, came to the rescue. She did indeed love Georgiana. But it was the love of a celebrity-stalker. She wanted to be Georgiana and possess everything she had, including the duke. Within a short space of time, Bess turned the Devonshires’ marriage into a ménage à trois, with herself at the centre. She was the duke’s mistress, Georgiana’s confidante and the social gatekeeper to Chatsworth. The arrival of two girls and a boy released Georgiana from her marital yoke, and from Bess to some extent. She took Charles Grey as her lover (the handsome Dominic Cooper in the film) and at last experienced the all-encompassing, romantic love that she had craved. The duke discovered the affair, however, after she became pregnant with Grey’s child. He banished Georgiana to the Continent for two years and forced her to relinquish the baby for adoption. Yet for all the damage Bess created and the lies she told, when forced to choose between Georgiana and the duke, she chose her friend. Bess supported Georgiana throughout her exile.

The film focuses on this period of Georgiana’s life. As a work of art rather than history, it makes sense because of the romantic intensity of the story. However, Georgiana lived for another 15 years. In fact, I treated her exile as one of several desperate moments in a narrative arc that began with her successful entry into fashionable society, veered off into a midlife descent into madness and exile, only to recover at the end with a triumphant return to public life.

I portrayed Georgiana as a brilliant, thwarted individual who used all available means to silence the voices in her head. To me, her exile was just another stop on the tortuous road to self-immolation. The nadir of her life, I believed, was in 1796, three years after her return. A mystery infection cost her the sight in one eye. The appalling treatment at the hands of 18th-century doctors cost Georgiana her looks. But it was also her redemption. Shorn of her last defence against the world, Georgiana entered a period of reflection and self-examination.

She re-entered society just when the Whig party was re-forming after two decades in the wilderness. Confident of her intellectual capabilities and no longer addicted to drugs or gambling, she resumed her political role. Georgiana died far too young, at 48. But it seemed to me as though her story had ended on the perfect note. She had proved George Eliot’s maxim that it is never too late to be what you might have been. Georgiana fitted the notions I had as a single woman in her twenties. Then, I assumed that no mistakes are permanent, and that we always have the freedom to remake ourselves. I believed that it is in our nature to strive towards some happy end point. That is how I wrote the narrative. I did not hide the sad times in Georgiana’s life, but they seemed insignificant beside her successes. Without doubt, this was the story that she would have preferred to be written, and I was so in thrall to her that I willingly went along with it.

What I had failed to do was look beyond her words to what she didn’t say; to look behind the pretty curtain. She couldn’t bear to do it herself, and I hadn’t experienced enough of life to know that she had erected a facade to protect her children from her pain. Ten years and five children later, if I were to write Georgiana today, I would give her a different narrative arc. I would acknowledge what the film succeeds in showing so elegantly — that the true heroine was not the politician or the fashion maven but the woman who wrote: “I have, in leaving Grey forever, left my heart and soul. He has one consolation, that I have given him up for my children only.”

There is no doubt in my mind, now, that the great tragedy of Georgiana’s life was her banishment from the children. This, not her illness, was the moment of truth. The duke essentially kidnapped her children in revenge for her love affair. His brutal assertion of male right forced Georgiana to redefine herself; from that moment, her life was no longer about possibilities but about consequences.

The casualties of her struggle for happiness were all around her: a child who would grow up thinking she was an orphan, an older daughter whose self-confidence would never recover, another daughter who treated her with suspicion for years, and a son who lost his hearing in her absence. Georgiana was a stranger to them when she returned, particularly to the younger ones. The overwhelming emotion she felt for the next decade was guilt.

Georgiana did undergo a personal redemption, and she did re-emerge into society on a triumphant wave of Whig politics. But underneath the patina of success were many, many layers of sadness. First and foremost, she had reached for freedom and been irrevocably harmed in the attempt. Like any modern woman, she had desperately wanted to feel fulfilled in all aspects of her life — as an ambitious individual, a woman who loved and was loved in return, and as a caring mother. She learnt in the most agonising way that the equation is impossible.

Shortly after Georgiana’s death, Harriet, her sister, wrote about “the latter miserable years of Georgiana’s life”. I still think that is an overly pessimistic judgment, borne on a wave of grief. But I see now that Georgiana’s pain never went away. Once she became a mother, her destiny, and her heart, belonged to the children. Everything she did after her exile was, for the most part, for them. It was a sacrifice she willingly made. Most mothers, including myself, would do the same. It is blindingly obvious to me now.

“Oh my beloved, my adored departed mother,” wrote her eldest daughter in the days after Georgiana’s death. “You whom I loved with such tenderness, you who were the best of mothers, adieu — I wanted to strew violets over her dying bed as she strewed sweets over my life, but they would not let me.”

The Duchess is released on September 5.

Copyright© 2008 Amanda Foreman