From sulfur to DDT, farmers have spent millennia looking for ways to stop crop-destroying insects.

April 20, 2023

The scientific breakthroughs of the 17th century, such as the compound microscope, made the natural world more intelligible and therefore controllable. By the 18th century, a farmer’s arsenal included nicotine, mercury and arsenic-based insecticides.

The Mesopotamians realized the necessity for pest control as early as 2500 B.C.E. They were fortunate to have access to elemental sulfur, which they made into a powder or burned as fumes to kill mites and insects. Elsewhere, farmers experimented with biological weaponry. The predatory ant Oecophylla smaragdina feasts on the caterpillars and boring beetles that destroy citrus trees. Farmers in ancient China learned to plant colonies next to their orange groves and tie ropes between branches, enabling the ants to spread easily from tree to tree.

The scientific breakthroughs of the 17th century, such as the compound microscope, made the natural world more intelligible and therefore controllable. By the 18th century, a farmer’s arsenal included nicotine, mercury and arsenic-based insecticides.

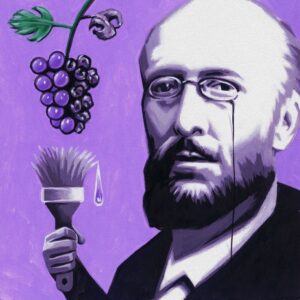

Illustration: Thomas Fuchs

But the causes of fungal blight remained a mystery. In 1843, the pathogen behind potato late blight, Phytophthora infestans, jumped from South America to New York and Philadelphia, and then crossed the Atlantic. Ireland had all the ingredients for an agricultural catastrophe: cool, wet winters, water-retaining clay soil, and reliance on a single potato variety as a food staple, combined with the custom of storing old and new potato crops together. Four years of heavily infected harvests, made worse by the British government’s failed response to the emergency, led to more than a million deaths.

In the 1880s, French vineyards were under attack from a different blight, Uncinula necator. By a happy coincidence, Pierre Marie Alexis Millardet, a botany professor at the University of Bordeaux, noticed that some grape vines growing next to a country road were free of the powdery mildew, while those further away were riddled with it. The owner explained that he had doused the roadside vines with a mix of copper sulfate and lime to deter casual picking. Armed with this knowledge, in 1885 Millardet perfected the Bordeaux mixture, the first preventive fungicide, which is still used today.

At the same time, an American entomologist named Albert Koebele was experimenting with biological pest controls. Citrus trees were once again under attack, only now it was the cottony cushion scale insect. Koebele went to Australia in 1888 and brought back its best-known predator, the vedalia beetle, thereby saving California’s citrus industry.

In 1936, the development of DDT, the first synthetic insecticide, was hailed as a miracle of science, offering the first real defense against malaria and other insect-borne diseases. But it was later discovered to be toxic to animals and humans, and it killed insects indiscriminately. Among its many victims was the vedalia beetle, which led to a resurgence of cottony cushion scale. Ultimately, the Environment Protection Agency banned DDT’s use in 1972.