The food service industry will eventually overcome the pandemic, just as it bounced back from ancient Roman bans and Prohibition.

September 24, 2020

It remains anyone’s guess what America’s once-vibrant restaurant scene will look like in 2021. At the beginning of this year, there were 209 Michelin-starred restaurants in the U.S. This month, the editors of the Michelin Guide announced that just 29 had managed to reopen after the pandemic lockdown.

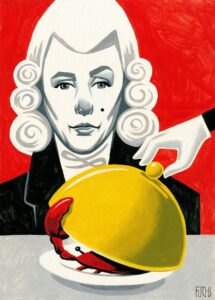

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

The food-service industry has always had to struggle. In the Roman Empire, the typical eatery was the thermopolium, a commercial kitchen that sold mulled wine and a prepared meal—either to-go or, in larger establishments, to eat at the counter. They were extremely popular among the working poor—archaeologists have found over 150 in Pompeii alone—and therefore regarded with suspicion by the authorities. In 41 A.D., Emperor Claudius ordered a ban on thermopolia, but the setback was temporary at best.

In Europe during the Middle Ages, the “cook shop” served a similar function for the poor. For the wealthier sort, however, it was surprisingly difficult to find places to eat out. Only a few monasteries and taverns provided hospitality. In Geoffrey Chaucer’s 14th-century comic travelogue “The Canterbury Tales,” the pilgrims have to bring their own cook, Roger of Ware, who is said to be an expert at roasting, boiling, broiling and frying.

To experience restaurant-style dining with separate tables, waiters and a menu, one had to follow in the footsteps of the Venetian merchant Marco Polo to the Far East. The earliest prototype of the modern restaurant developed in Kaifeng, the last capital of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), to accommodate its vast transient population of merchants and officials. The accumulation of so many rich and homesick men led to a boom in sophisticated eateries offering meals cooked to order.

Europe had nothing similar until the French began to experiment with different forms of public catering in the 1760s. These new places advertised themselves as a healthy alternative to the tavern, offering restorative soups and broths—hence their name, the restaurant.

In 1782, this rather humble start inspired Antoine Beauvilliers to open the first modern restaurant, La Grande Taverne de Londres, which unashamedly replicated the luxury of royal dining. By the 1800s, the term “restaurant” in any language meant a superior establishment serving refined French cuisine.

In 1830, two Swiss brothers, John and Peter Delmonico, opened the first restaurant in the U.S., Delmonico’s in New York. It was a temple of haute cuisine, with uniformed waiters, imported linens and produce grown on a dedicated farm. What’s more, diners could make reservations ahead of time and order either a la carte or prix fixe—all novel concepts in 19th century America.

Delmonico’s reign lasted until Prohibition, which forced thousands of U.S. restaurants out of business, unable to survive without alcohol sales. During that time, the only growth in the restaurant trade was in illegal speakeasies and family-friendly diners. Yet in 1934, just one year after Prohibition’s repeal, the art deco-themed Rainbow Room opened its doors at Rockefeller Plaza in New York. Out of the ashes of the old, a new age of elegance had begun.