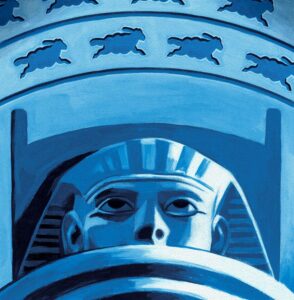

People have been pursuing the secrets of slumber ever since the ancient Egyptians opened sacred ‘sleep clinics.’

March 24, 2023

It is a riddle worthy of the Sphinx: What is abundant and yet in short supply, free and yet frequently paid for, necessary for life and yet resembles death? The answer is sleep. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than a third of Americans are sleep deprived.

Worries about sleeplessness also kept the ancient Egyptians up at night. They recognized its importance, and many of their methods for treating insomnia are still used today. Smelling or applying lavender oil was the first recommendation. Failing that, there was drinking camomile tea or taking a narcotic such as opium. The Egyptians also invented the sleep clinic. Among the medical services offered by priests was a night in a sacred chamber, where special rituals might send patients into a deep sleep in the hope of receiving a curative visitation from a god.

Ancient Indian and Chinese physicians treated sleep disorders with herbs such as Indian winter cherry, known as ashwagandha, and Korean red ginseng. But they also advocated practical measures to encourage the body to sleep, such as chanting, burning incense and, in the case of the Chinese, choosing the right kind of bed.

Greek physicians copied the practice of divine healing through ritualized sleep practices, calling it “incubation.” But Greek philosophers were puzzled by sleep, since it seemed to defy categorization. Ever the pragmatist, Aristotle decided in his treatise “On Sleep and Sleeplessness” that sleep was connected to digestion, the final stage of the whole complicated process.

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

It turns out, however, that ancient prescriptions were based on a different model for sleeping than the one we use today. The historian A. Roger Ekirch has argued that before industrialization changed the workday, most societies practiced segmented sleep—sleeping in two shifts with a break in the middle. Waking up and thinking or futzing for a couple of hours was considered both normal and welcome.

In the 14th century, new translations of ancient Greek and Persian medical texts gave European physicians fresh insights into sleep conditions. Scientists looked for alternatives to overcome insomnia, with laudanum becoming the gold standard after the 16th century Swiss-German physician Paracelsus discovered how to dilute opium’s active ingredients in alcohol.

Another important question was how much control a person has over their actions while asleep. Pope Clement V, who took office in 1305, was the first pope to absolve Christians of sinful acts committed while sleepwalking. Centuries later, in 1846, a Boston jury acquitted Albert Tirrell of killing his mistress Mary Bickford, who was found in bed with her throat cut, on the grounds that he was a habitual sleepwalker with a history of somnambulistic violence.

The science of sleep had hardly advanced by 1925, when physiologist Nathaniel Kleitman persuaded the University of Chicago to fund the world’s first sleep laboratory. Helped by a team of students and test subjects that included his own family, Kleitman showed that sleep could be subjected to the same rigorous experiments as any other condition. He discovered REM sleep, which is when dreams occur, as well as the internal body clock and the effects of prolonged sleeplessness. Kleitman demystified the mechanics of sleep but not, alas, the alchemy behind the perfect night’s sleep.