WSJ Historically Speaking: HMS Terror—and the Moral Challenge of Exploration

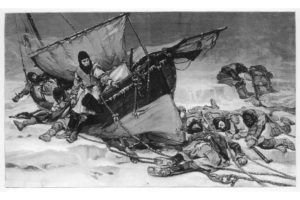

Engraving showing the end of Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated Arctic expedition of 1845 entitled ‘They Forged the last link with their lives’. This engraving was taken from a painting by W. Thomas Smith exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1896. PHOTO: MARY EVANS/ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS LTDT/EVERETT COLLECTION

Earlier this month, searchers found the HMS Terror beneath the Canadian Arctic ice, solving one of the most famous mysteries in maritime history. The ship was part of an expedition led by Sir John Franklin that vanished in the 1840s while trying to locate the Northwest Passage.

The disappearance inspired more than 50 search expeditions, as well as an outpouring of literature. Charles Dickens had a major hand in a stage production about the disaster, and an elegy by the poet Algernon Swinburne, “The Death of Sir John Franklin,” asked poignantly, “Is this the end?”

Ironically, the discovery of Franklin’s long-lost ship coincided with the 100th anniversary of the attempt of Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922) to cross the Antarctic via the South Pole in 1914-16. The two polar expeditions resembled each other in many ways. Both were scientific endeavors that came to grief when their ships became icebound. But while Shackleton undertook a daring 800-mile journey in an open lifeboat to rescue his stranded crew, Franklin died shortly after the initial disaster and his crew had to fend for themselves. Evidence suggests that the men, doomed by lead poisoning from the ship’s food and water supply, descended into starvation, madness and ultimately cannibalism.

Willingly risking life and limb just to explore the great unknown would have been incomprehensible to the ancient Egyptians and Greeks. They preferred to make new trading partners rather than new discoveries. Nor were their ships designed for long voyages on the open sea.

Pytheas of Massalia (who lived around 300 B.C.) may have been the first Greek to sail as far north as the British Isles. Raised in what is today Marseille, France, he may even have reached the coast of Norway. But it’s likely that others had already mapped out the route. This ancient caution had an impact: As the French novelist André Gide observed, “One doesn’t discover new lands without being willing to lose sight, for a very long time, of the shore.”

With rare exceptions, like the Vikings’ travels to eastern Canada around 1000, exploration only became possible with the development of the dry maritime compass around 1300, followed by faster and more agile ships in the late 15th century. Early Renaissance mariners had the means to go anywhere, but most were less interested in expanding human knowledge than in finding a more direct route for the lucrative spice trade with India.

A few of the giants of early modern exploration achieved fame and riches. But many faced wretched and lonely deaths in some corner of a far-off land. Ferdinand Magellan, the first circumnavigator of the globe, bled to death on a beach in the Philippines in 1521 after running into trouble with a local tribe.

The Victorians were the first to give exploration the mantra of a moral purpose. “To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield,” wrote Alfred, Lord Tennyson in his poem “Ulysses,” fueling the popular view of such exploits as a lofty combination of faith, patriotism and scientific inquiry. Shackleton himself gave perfect expression to these ideals. Though the Endurance expedition had failed, he wrote in his memoirs, it had achieved something greater: “We had reached the naked soul of man.”