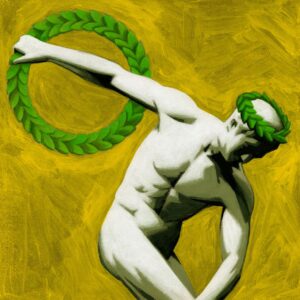

Before they became a holiday symbol, wreaths were used to celebrate Egyptian gods, victorious Roman generals and the winter solstice.

On Christmas Eve, 1843, three ghosts visited Ebenezer Scrooge in the Charles Dickens novella “A Christmas Carol” and changed Christmas forever. Dickens is often credited with “inventing” the modern idea of Christmas because he popularized and reinvigorated such beloved traditions as the turkey feast, singing carols and saying “Merry Christmas.”

But one tradition for which he cannot take credit is the ubiquitous Christmas wreath, whose pedigree goes back many centuries, even to pre-Christian times.

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

Wreaths can be found in almost every ancient culture and were worn or hung for many purposes. In Egypt, participants in the festival of Sokar, a god of the underworld, wore onion wreaths because the vegetable was venerated as a symbol of eternal life. The Greeks awarded laurel wreaths to the winners of competitions because the laurel tree was sacred to Apollo, the god of poetry and athletics. The Romans bestowed them on emperors and victorious generals.

Fixing wreaths and boughs onto doorposts to bring good luck was another widely practiced tradition. As early as the 6th century, Lunar New Year celebrants in central China would decorate their doors with young willow branches, a symbol of immortality and rebirth.

The early Christians did not, as might be assumed, create the Yuletide wreath. That was the pagan Vikings. They celebrated the winter solstice with mistletoe, evergreen wreaths made of holly and ivy, and 12 days of feasting, all of which were subsequently turned into Christian symbols. Holly, for example, has often been equated with the crown of thorns. Perhaps not surprisingly for the people who also introduced the words “knife,” “slaughter” and “berserk,” one Viking custom involved setting the Yuletide wreath on fire in the hope of attracting the sun’s attention.

Across northern Europe, the Norse wreath was eventually absorbed into the Christian calendar as the Advent wreath, symbolizing the four weeks before Christmas. It became part of German culture in 1839, when Johann Hinrich Wichern, a Lutheran pastor in Hamburg, captured the public’s imagination with his enormous Advent wreath. Made with a cartwheel and 24 candles, it was intended to help the children at his orphanage count the days to Christmas.

German immigrants to the U.S. brought the Advent wreath with them. Still, while Americans might accept a candlelit wreath inside the house, door wreaths were rare, especially in former Puritan strongholds such as Boston. The whiff of disapproval hung about until 1935, when Colonial Williamsburg appointed Louise B. Fisher, an underemployed and overqualified professor’s wife, to be its head of flowers and decorations. Inspired by her love of 15th-century Italian art, Fisher allowed her wreath designs to run riot on the excuse that she was only adding fruits and other whimsies that had been available during the Colonial era.

Thousands of visitors saw her designs and returned home to copy them. Like Wichern, she helped inspire a whole generation to be unapologetically joyous with their wreaths. Thanks in part to her efforts, America’s front doors are a thing to behold at this time of year, proving that it’s never too late to pour new energy into an old tradition.