Historically Speaking: At Age 50, a Time of Second Acts

Amanda Foreman finds comfort in countless examples of the power of reinvention after five decades.

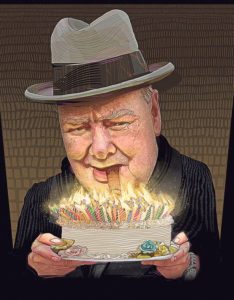

ILLUSTRATION BY TONY RODRIGUEZ

In Russia many centuries later, the general Mikhail Kutuzov was in his 60s when his moment came. In 1805, Czar Alexander I had unfairly blamed Kutuzov for the army’s defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz and relegated him to desk duties. Russian society cruelly treated the general, who looked far from heroic—a character in Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” notes the corpulent Kutuzov’s war scars, especially his “bleached eyeball.” But when the country needed a savior in 1812, Kutuzov, the “has-been,” drove Napoleon and his Grande Armée out of Russia.

Winston Churchill had a similar apotheosis in World War II when he was in his 60s. Until then, his political career had been a catalog of failures, the most famous being the Gallipoli Campaign of 1916 that left Britain and its allies with more than 100,000 casualties.

As for writers and artists, they often find middle age extremely liberating. They cease being afraid to take risks in life. Another Fitzgerald—the Man Booker Prize-winning novelist Penelope—lived on the brink of homelessness, struggling as a tutor and teacher (she later recalled “the stuffy and inky boredom of the classroom”) until she published her first book at 58.

Anna Mary Robertson Moses, better known as Grandma Moses, may be the greatest example of self-reinvention. After many decades of farm life, around age 75 she began a new career, becoming one of America’s best known folk painters.