Historically Speaking: Boycotts that Brought Change

Modern rights movements have often used the threat of lost business to press for progress

November 12, 2021

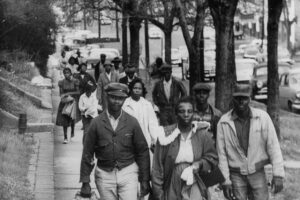

Sixty-five years ago, on Nov. 13, 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Browder v. Gayle, putting an end to racial segregation on buses. The organizers of the Montgomery bus boycott, which had begun shortly after Rosa Park s’s arrest on Dec. 1, 1955, declared victory and called off the campaign as soon as the ruling came into effect. But that was only the beginning. As the Civil Rights Movement progressed, boycotts of businesses that supported segregation became a regular—and successful—feature of Black protests.

Boycotts are often confused with other forms of protest. At least four times between 494 and 287 B.C., Rome’s plebeian class marched out of the city en masse, withholding their labor in an effort to win more political rights. Some historians describe this as a boycott, but it more closely resembled a general strike. A better historical precedent is the West’s reaction to Sultan Mehmed II’s imposition of punitive taxes on Silk Road users in 1453. European traders simply avoided the overland networks via Constantinople in favor of new sea routes, initiating the so-called Age of Discovery.

The first modern boycotts began in the 18th century. Britain increased taxes on its colonial subjects following the Seven Years War in 1756-1763, inciting a wave of civil disobedience. Merchants in Philadelphia, New York and Boston united to boycott British imports. Together with intense political lobbying by Benjamin Franklin among others, the boycott resulted in the levies’ repeal in 1766. Several years later, London again tried to raise revenue through taxes, touching off a more famous boycott, during which the self-styled Sons of Liberty dumped the contents of 342 tea chests into Boston Harbor on Dec. 16, 1773.

In 1791 the British abolitionist movement instigated a national boycott of products made by enslaved people. As many as 300,000 British families stopped buying West Indian sugar, causing sales to drop by a third to half in some areas. Although the French Revolutionary Wars stymied this campaign, its early successes demonstrated the power of consumer protest.

Despite the growing popularity of the action, the term “boycott” wasn’t used until 1880. It was coined in Ireland as part of a campaign of civil disobedience against absentee landowners. Locals turned Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott, an unpopular land agent in County Mayo for the Earl of Erne, into a pariah. His isolation was so complete that the Boycott family relocated to England. The “boycott” of Boycott not only garnered international attention but inspired imitators.

Boycotts enabled oppressed people around the world to make their voices heard. But the same tool could also be a powerful weapon in the hands of oppressors. During the late 19th century in the American west, Chinese workers and the businesses that hired them were often subject to nativist boycotts. In 1933, German Nazi party leaders organized a nationwide boycott of Jewish-owned business in the lead-up to the passage of a law barring Jews from public sector employment.

Despite the potential for misuse, the popularity of economic and political boycotts increased after World War II. In January 1957, shortly after the successful conclusion of the Montgomery bus boycott, black South Africans in Johannesburg started their own bus boycott. From this local protest grew a national and then international boycott movement that continued until South Africa ended apartheid in 1991. Sometimes the penny, as well as the pen, is more powerful than the sword.