WSJ Historically Speaking: The Perils of Cultural Purity

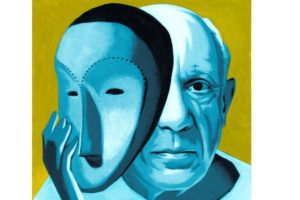

PHOTO: THOMAS FUCHS

“Cultural appropriation” is a leading contender for the most overused phrase of 2017. Originally employed by academics in postcolonial studies to describe the adoption of one culture’s creative expressions by another, the term has evolved to mean the theft or exploitation of an ethnic culture or history by persons of white European heritage.

The accusation of cultural appropriation is now having a chilling effect on cultural life itself. In Canada, editors of two different magazines resigned in recent months amid controversies for voicing their support of creative cultural borrowing. In the U.S., protests in Minnesota against the Walker Art Center led to the dismantling of “Scaffold,” a sculpture by the white artist Sam Durant, which referenced, among other victims, the 1862 execution of 38 Native Americans of the Dakota people.

It’s a lamentable trend. As history bountifully attests, all cultures have borrowed and exchanged ideas with one another. Sometimes the exchange has been between equal powers, and sometimes not. Either way—whether it’s the Japanese adoption of Chinese literary culture in the ninth century, the American Transcendentalists’ embrace of Hindu thought in the 19th century or the influence of African sculpture on Pablo Picasso —there’s no getting away from the fact that one man’s cultural appropriation is another man’s appreciation.

The Romans still hold the world record for appropriating culture, enthusiastically basing their own, from law to literature, on the Greeks. In the 4th century A.D., Rome sealed its championship by appropriating the religion of a tiny minority culture in the Middle East—thus introducing Christianity to much of the world. The appropriation wasn’t all one way, however. The image of Jesus as “the good shepherd” may have evolved from the Greco-Roman god Hermes/Mercury, who was often shown with a ram across his shoulders. Likewise, early Christian imagery of the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus echoes ancient Egyptian depictions of the goddess Isis with the godchild Horus on her lap.

Both ancient Rome and early Christianity demonstrate how cultural appropriation produces growth and innovation. By contrast, the fate of societies that have embraced the ideology of cultural separatism offers up a cautionary tale of decline.

In 529, Justinian I—the Christian emperor of Byzantium, which had inherited the eastern part of the Roman Empire—closed down the Neoplatonic Academy in Athens, ending a 900-year-old tradition of philosophical inquiry. The blow to Western culture was immense. Only with the founding of the University of Bologna in 1088 did Christian Europe begin to rebuild higher education.

Almost 500 years later, Emperor Jiajing of China was guilty of similar folly when he ordered the destruction of all oceangoing ships. The edict effectively sealed his subjects inside China’s borders. Instead of protecting the status quo against foreign ideas and money, as Jiajing had intended, his action helped to precipitate China’s descent from being the world’s richest and most powerful nation in the 15th century into a cultural and economic backwater by the 19th.

The same shortsightedness can be seen in the Ottoman Empire’s 1515 ban on printing in Arabic, because the printed word would defile God’s name, and in the Spanish Inquisition, which focused on religious purity at the expense of every other cultural good. Today’s cultural-appropriation thought police might want to recall that some victories are worse than defeats.