From prisoners to exiles to marooned sailors, human beings have faced the ordeal of enforced solitude.

Being one’s own company can be blissful, but not when it’s involuntary. According to John Donne, the 17th-century English poet and priest, “As sickness is the greatest misery, so the greatest misery of sickness is solitude.” Now that nearly two in three Americans are currently subject to shelter-in-place orders as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, how will we cope with prolonged isolation?

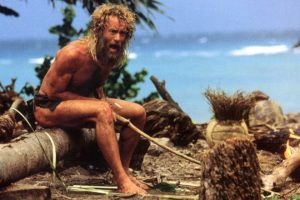

Tom Hanks in the 2000 movie ‘Cast Away.’

PHOTO: EVERETT COLLECTION

The Germans have a special word for feeling utterly alone and isolated: mutterseelenallein, a compound that literally means “mother’s souls alone.” According to one theory, the word entered the German language as a misinterpretation of the French phrase moi teut seul (“me all alone”), which was used by the Huguenots—French Protestants who fled to Berlin in the 18th century to escape persecution at home.

Although the ancients didn’t have an equivalent word, they certainly knew the feeling. In 44 B.C., the Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero was declared an enemy of the state and forced into hiding. Despite his loneliness, or perhaps because of it, Cicero used the time to write his final work, “On Duties,” in only four weeks.

We can’t all be like Cicero, of course, and write a masterpiece while on lockdown. But we can certainly rise to the occasion and surprise ourselves. One of the least likely castaways in history was the wealthy French aristocrat Marguerite de La Rocque de Roberval, who in 1542 agreed to accompany her spendthrift cousin Jean-Francois de Roberval on a voyage to New France, modern Canada. The jolly adventure became a nightmare after Roberval accused Marguerite of sexual immorality while on board his ship. This was his flimsy excuse for marooning her along with her maid and lover on the deserted Isle of Demons off Newfoundland.

Marguerite’s lover and their baby soon succumbed, as did her maid, leaving the hitherto pampered heiress to survive in the wilderness as best she could. During her two years as a castaway she killed a bear, ate its carcass and turned its skin into clothing. After her rescue and return to France in 1544, Marguerite created a new life for herself as an educator. The treacherous Roberval escaped punishment, but was subsequently murdered by a mob in 1560.

Such stories provided ample material to Daniel Defoe, who wrote the ultimate social isolation story, “Robinson Crusoe,” in 1719. The novel has been adapted many times since, including for the 2000 film “Cast Away,” starring Tom Hanks as the Crusoe figure. Defoe based his tale in part on the real-life castaway Alexander Selkirk, a Royal Navy officer who in 1704 was abandoned by his shipmates on a deserted island in the south Pacific, where he managed to survive until he was rescued five years later.

Defoe himself knew something about prolonged isolation: In 1703, he was imprisoned for several months after he published a pamphlet satirizing the Church of England. Defoe’s stint in prison made him a better advocate for the social outcasts he described in his novels, just as Crusoe’s 28-year sojourn on the island made him into a better person—a man of faith and purpose rather than the malcontent of his former life. “No man is an island entire of itself,” wrote Donne; being human makes us all connected, no matter where we are.