Americans have long debated the value of take-home assignments, but children have been struggling with them for millennia.

February 24, 2023

If American schoolchildren no longer had to do hours of homework each night, a lot of dogs might miss out on their favorite snack, if an old excuse is to be believed, but would the children be worse off? Americans have been debating whether or not to abolish homework for almost a century and a half. Schoolwork and homework became indistinguishable during Covid, when children were learning from home. But the normal school day has returned and so has the issue.

The ancient Greek philosophers thought deeply about the purpose of education. In the Republic, Plato argued that girls as well as boys should receive physical, mental and moral training because it was good for the state. But the Greeks were less concerned about where this training should take place, school or home, or what kind of separation should exist between the two. The Roman statesman Cicero wrote that he learned at home as much as he did outside of it.

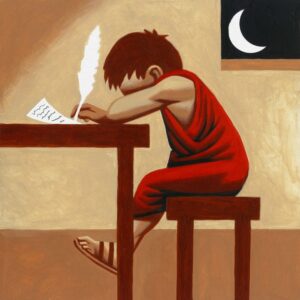

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

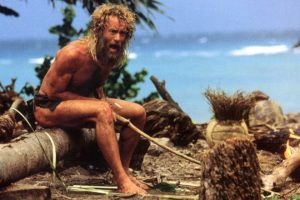

But, of course, practice makes perfect, as Pliny the Younger told his students of oratory. Elementary schoolchildren in Greco-Roman Egypt were expected to practice their letters on wax writing tablets. A homework tablet from the second century AD, now in the British Museum, features two lines of Greek written by the teacher and a child’s attempt to copy them underneath.

Tedious copying exercises also plagued the lives of ancient Chinese students. In 1900 an enormous trove of 1500 to 900-year-old Buddhist scrolls was discovered in a cave near Dunhuang in northwestern China. Scattered among the texts were homework copies made by bored monastery pupils who scribbled things like, “This is Futong incurring another person’s anger.”

What many people generally think of as homework today—after-class assignments forced on children regardless of their pedagogical usefulness—has its origins in the Prussian school system. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Prussia led the world in mass education. Fueled by the belief that compulsory schooling was the best means of controlling the peasantry, the authorities devised a rigorous system based on universal standards and applied methods. Daily homework was introduced, in part because it was a way of inserting school oversight, and by extension the state, into the home.

American educationalists such as Horace Mann in Massachusetts sought to create a free school system based on the Prussian model. Dividing children into age groups and other practical reforms faced little opposition. But as early as 1855, the American Medical Monthly was warning of the dangers to children’s health from lengthy homework assignments. In the 1880s, the Boston school board expressed its concern by voting to reduce the amount of arithmetic homework in elementary schools.

As more parents complained of lost family time and homework wars, the Ladies’ Home Journal began to campaign for its abolition, calling after-school work a “national crime” in 1900. The California legislature agreed, abolishing all elementary school homework in 1901. The homework debate seesawed until the Russians launched Sputnik in 1957 and shocked Americans out of complacency. Congress quickly passed a $1 billion education spending program. More, not less, homework became the mantra until the permissive ‘70s, only to reverse in response to Japan’s economic ascendancy in the ‘80s.

All the old criticisms of homework remain today, but perhaps the bigger threat to such assignments is technological, in the form of the universal homework butler known as ChatGPT.