From King Solomon to the Shah of Persia, rulers have used stately seats to project power.

The Wall Street Journal, April 22, 2019

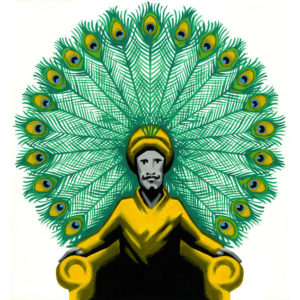

ILLUSTRATION BY THOMAS FUCHS

“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown,” complains the long-suffering King Henry IV in Shakespeare. But that is not a monarch’s only problem; uneasy, too, is the bottom that sits on a throne, for thrones are often a dangerous place to be. That is why the image of a throne made of swords, in the HBO hit show “Game of Thrones” (which last week began its eighth and final season), has served as such an apt visual metaphor. It strikingly symbolizes the endless cycle of violence between the rivals for the Iron Throne, the seat of power in the show’s continent of Westeros.

In real history, too, virtually every state once put its leader on a throne. The English word comes from the ancient Greek “thronos,” meaning “stately seat,” but the thing itself is much older. Archaeologists working at the 4th millennium B.C. site of Arslantepe, in eastern Turkey, where a pre-Hittite Early Bronze Age civilization flourished, recently found evidence of what is believed to be the world’s oldest throne. It seems to have consisted of a raised bench which enabled the ruler to display his or her elevated status by literally sitting above all visitors to the palace.

Thrones were also associated with divine power: The famous 18th-century B.C. basalt stele inscribed with the law code of King Hammurabi of Babylon, which can be seen at the Louvre, depicts the king receiving the laws directly from the sun god Shamash, who is seated on a throne.

Naturally, because they were invested with so much religious and political symbolism, thrones often became a prime target in war. According to Jewish legend, King Solomon’s spectacular gold and ivory throne was stolen first by the Egyptians, who then lost it to the Assyrians, who subsequently gave it up to the Persians, whereupon it became lost forever.

In India, King Solomon’s throne was reimagined in the early 17th century by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan as the jewel-and-gold-encrusted Peacock Throne, featuring the 186-carat Koh-i-Noor diamond. (Shah Jahan also commissioned the Taj Mahal.) This throne also came to an unfortunate end: It was stolen during the sack of Delhi by the Shah of Iran and taken back to Persia. A mere eight years later, the Shah was assassinated by his own bodyguards and the Peacock Throne was destroyed, its valuable decorations stolen.

Perhaps the moral of the story is to keep things simple. In 1308, King Edward I of England commissioned a coronation throne made of oak. For the past 700 years it has supported the heads and backsides of 38 British monarchs during the coronation ceremony at Westminster Abbey. No harm has ever come to it, save for the pranks of a few very naughty choir boys, one of whom carved on the back of the throne: “P. Abbott slept in this chair 5-6 July 1800.”