How the marathon became the world’s top endurance race

September 2, 2021

The New York City Marathon, the world’s largest, will hold its 50th race this autumn, after missing last year’s due to the pandemic. A podiatrist once told me that he always knows when there has been a marathon because of the sudden uptick in patients with stress fractures and missing toenails. Nevertheless, humans are uniquely suited to long-distance running.

Some 2-3 million years ago, our hominid ancestors began to develop sweat glands that enabled their bodies to stay cool while chasing after prey. Other mammals, by contrast, overheat unless they stop and rest. Thus, slow but sweaty humans won out over fleet but panting animals.

The marathon, at 26.2 miles, isn’t the oldest known long-distance race. Egyptian Pharaoh Taharqa liked to organize runs to keep his soldiers fit. A monument inscribed around 685 B.C. records a two-day, 62-mile race from Memphis to Fayum and back. The unnamed winner of the first leg (31 miles) completed it in about four hours.

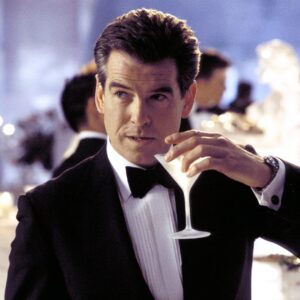

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

The considerably shorter marathon derives from the story of a Greek messenger, Pheidippides, who allegedly ran from Marathon to Athens in 490 B.C. to deliver news of victory over the Persians—only to drop dead of exhaustion at the end. But while it is true that the Greeks used long-distance runners, called hemerodromoi, or day runners, to convey messages, this story is probably a myth or a conflation of different events.

Still, foot-bound messengers ran impressive distances in their day. Within 24 hours of Herman Cortes’s landing in Mexico in 1519, messenger relays had carried news of his arrival over 260 miles to King Montezuma II in Tenochtitlan.

As a competitive sport, the marathon has a shorter history. The longest race at the ancient Olympic Games was about 3 miles. This didn’t stop the French philologist Michel Bréal from persuading the organizers of the inaugural modern Olympics in 1896 to recreate Pheidippides’s epic run as a way of adding a little classical flavor to the Games. The event exceeded his expectations: The Greek team trained so hard that it won 8 of the first 9 places. John Graham, manager of the U.S. Olympic team, was inspired to organize the first Boston Marathon in 1897.

Marathon runners became fitter and faster with each Olympics. But at the 1908 London Games the first runner to reach the stadium, the Italian Dorando Pietri, arrived delirious with exhaustion. He staggered and fell five times before concerned officials eventually helped him over the line. This, unfortunately, disqualified his time of 2:54:46.

Pietri’s collapse added fuel to the arguments of those who thought that a woman’s body could not possibly stand up to a marathon’s demands. Women were banned from the sport until 1964, when Britain’s Isle of Wight Marathon allowed the Scotswoman Dale Greig to run, with an ambulance on standby just in case. Organizers of the Boston Marathon proved more intransigent: Roberta Gibb and Katherine Switzer tried to force their way into the race in 1966 and ’67, but Boston’s gender bar stayed in place until 1972. The Olympics held out until 1984.

Since that time, marathons have become a great equalizer, with men and women on the same course: For 26.2 miles, the only label that counts is “runner.”