Over the centuries, lucky discoveries depend on training and discernment

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

One recent example comes from an international scientific team studying the bacterium, Ideonella sakaiensis 201-F6, which makes an enzyme that breaks down the most commonly used form of plastic, thus allowing the bacterium to eat it. As reported last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, in the course of their research the scientists accidentally created an enzyme even better at dissolving the plastic. It’s still early days, but we may have moved a step closer to solving the man-made scourge of plastics pollution.

The development illustrates a truth about seemingly serendipitous discoveries: The “serendipity” part is usually the result of years of experimentation—and failure. A new book by two business professors at Wharton and a biology professor, “Managing Discovery in the Life Sciences,” argues that governments and pharmaceutical companies should adopt more flexible funding requirements—otherwise innovation and creativity could end up stifled by the drive for quick, concrete results. As one of the authors, Philip Rea, argues, serendipity means “getting answers to questions that were never posed.”

So much depends on who has observed the accident, too. As Joseph Henry, the first head of the Smithsonian Institution, said, “The seeds of great discoveries are constantly floating around us, but they only take root in minds well prepared to receive them.”

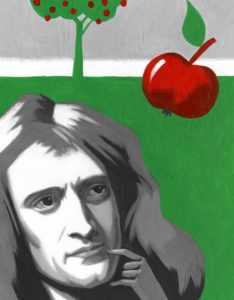

One famously lucky meeting of perception and conception happened in 1666, when Isaac Newton observed an apple fall from the tree. (The details remain hazy, but there’s no evidence that the fruit actually hit him, as legend has it.) Newton had seen apples fall before, of course, but this time the sight inspired him to ask questions about gravity’s relationship to the rules of motion that he was contemplating. Still, it took Newton another 20 years of work before he published his Law of Universal Gravitation.

Bad weather was the catalyst for another revelation, leading to physicist Henri Becquerel’s discovery of radioactivity in 1896. Unable to continue his photographic X-ray experiments on the effect of sunlight on uranium salt, Becquerel put the plates in a drawer. They developed, incredibly, without light. Realizing that he had been pursing the wrong question, Becquerel started again, this time focusing on uranium itself as a radiation emitter.

As for inventions, accident and inadvertence played a role in the development of Post-it Notes and microwave heating. During the 1990s, Viagra failed miserably in trials as a treatment for angina, but alert researchers at Pfizer realized that one of the side effects could have global appeal.

The most famous accidental medical discovery is antibiotics. The biologist Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928 after he went on vacation, leaving a petri dish of bacteria out in the laboratory. On his return, the dish had developed mold, with a clean area around it. Fleming realized that something in the mold must have killed off the bacteria.

That ability to ask the right questions can be more important than knowing the right answers. Funders of science should take note.