WSJ Historically Speaking: Ancient Automatons, Modern Worries

Earlier this year, Stephen Hawking was among the scientific luminaries who signed an open letter warning that artificial intelligence offered great benefits to humanity but also posed great risks to our safety. Today, Google’s DeepMind computer is capable of teaching itself how to play new videogames, but what if—some tomorrows down the line—it unilaterally tried something new, such as a war game using real nuclear weapons.

Humans have been experimenting with automatons for centuries, but it is only we moderns who have worried about the consequences. The Greeks saw nothing to fear from artificial life. In their mythology, the god Hephaestus was responsible for the creation of mechanized beings—from the golden slaves he designed for his personal use to the bronze giant Talos, who guarded the island of Crete. Stopping one of these machines was as simple as removing the plug and letting the ichor (immortal blood) run out.

The possibility of imitating the gods made the Greeks early experimenters in mechanical engineering. In the fifth century B.C., Archytas of Tarentum—the founder of mathematical mechanics—created a steam-powered wooden pigeon often considered the first robot in history. Three centuries later, unknown engineers created an astronomical calculator—the Antikythera Mechanism—so accurate that nothing would match it for the next thousand years.

Nor were the Greeks alone in their fascination with ingenious devices. The Chinese were also avid inventors and engineers. Among the most celebrated was the fifth century B.C. engineer King-Shu Tse, who designed a mechanical bird and even a machine horse that could jump.

By the Middle Ages, the spirit of invention was moving west. Al-Jazari of Diyarbakir, in today’s Turkey, was probably the greatest scientific genius of the 13th century. In 1206, he published “The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices,” which contained instructions for building dozens of gadgets. He designed his most famous automatons—a band of mechanical musicians—for the bey of Artuklu, Nasreddin Muhammad. Whenever the bey entertained at the palace, al-Jazari would amuse the guests by sending the musicians out on a boat to serenade them.

Three hundred years later, Leonardo da Vinciperformed a similar feat for the French King François I, building a lion automaton that could rear up on its hind legs. By the 18th century, automatons were everywhere, from a defecating duck made by Jacques de Vaucanson to “Tipu’s Tiger,” an automaton designed for a sultan in India, featuring a tiger in the act of mauling a nearly life-size European soldier.

Only after Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel “Frankenstein” did some start to wonder whether humanity’s fascination with artifice and science might backfire. “Why did I live?” cries Shelley’s monster. “My feelings were those of rage and revenge.”

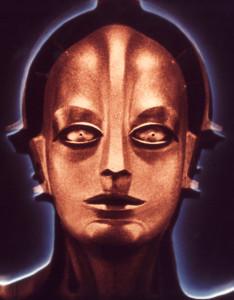

As engineering accelerated, so did people’s anxieties about mechanized beings. In 1893, the American writer Ambrose Biercecrystallized those fears in “Moxon’s Master,” a short story about a chess-playing automaton that murders its master. Three decades later, the Czech playwright Karel Capek wrote “Rossum’s Universal Robots,” which both coined the word “robot” and started the meme that artificially intelligent beings might rebel. In his 1927 film “Metropolis,” the directorFritz Lang took the idea further with Maria, the evil “machinenmensch” (machine human) whose lifelike appearance makes her undetectable.

We are still far from creating cyborgs. But as Prof. Hawking warned in a recent BBC interview, an intelligent machine “could take off on its own and redesign itself at an ever-increasing rate.” Could we prevent a real generation of computers like Hal from “2001: A Space Odyssey” from deciding that what’s best for Earth is human extinction?