WSJ Historically Speaking: The “Unbroken Spirit” to Survive

Louis Zamperini was a U.S. Olympic runner, World War II hero and Japanese prison-‐camp survivor who went on to become a Christian motivational speaker. The extraordinary suffering and hardship that he endured to come home became the subject of Laura Hillenbrand’s best-‐selling biography “Unbroken” and Angelina Jolie’s recent film of the same title.

One reason why Zamperini resonates with audiences is because his story harks back to classical mythology. The qualities that enabled Zamperini to survive his epic journey—courage, resourcefulness and resilience—were highly prized by the ancient Greeks. A man who displayed them was said to possess arête, broadly defined as moral excellence in the course of fulfilling a specific purpose. For the Greeks, the original Zamperini was Odysseus, whose return to Ithaca after the battle of Troy cost him many arduous trials and lasted 10 years.

The late Victorians were fascinated by such manly virtue. The poet Rudyard Kipling composed his famous poem “If—” to celebrate it. The inspiration behind the poem was another citizen-soldier, the South African politician Leander Starr Jameson, whom Kipling thought had shown unparalleled courage and stoicism after a failed attack against the Boers.

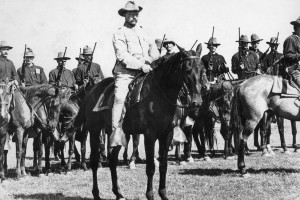

The greatest American exponent of this sort of virtue was PresidentTheodore Roosevelt. In his famous speech “The Strenuous Life,” Roosevelt captured, as few have before or since, the “highest form of success,” which comes “not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.”

After losing his 1912 bid to return to the White House, Roosevelt undertook a hazardous expedition to the Amazon basin. Hoping to recapture something of the spirit of Henry Hudson and Lewis and Clark, Roosevelt and the Brazilian explorer Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon set off to explore the River of Doubt, one of the great uncharted tributaries of the Amazon River.

Accidents, illness and hunger plagued the expedition all the way. At one point, an ailing Roosevelt offered to sacrifice himself to increase the chances of the team’s survival. Ultimately, he finished the journey with 16 of the original 19 members. The deaths were tragic, but Roosevelt wound up with a better record than Odysseus—who lost six men to the Cyclops Polyphemus, 11 of his 12 ships to the Laestrygonians and his last remaining ship to the whirlpool of Charybdis.

Sixty-two years after Roosevelt was tested by the Amazon, another group found itself fighting to stay alive in the harsh terrain of South America. In October 1972, Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, carrying 45 people, crashed into the Andes mountains. Twenty-seven survived the initial accident only to face hypothermia, starvation and avalanches. During the next two months, 11 more died. By then, the desperate survivors had resorted to cannibalism. The remaining 16 were saved by the courage of two men: Nando Parrado and Roberto Canessa, who eventually set off in the bitter cold to seek help.

Lost and starving, Parrado and Canesso trekked through the wilderness for 10 days. They finally stopped when a river blocked their passage. Canesso lay down to die. Parrado, hardly in better shape, doggedly crawled to his knees—and managed to attract the attention of a passing horseman.

As Kipling wrote: “If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew / To serve your turn long after they are gone, / And so hold on when there is nothing in you,” you will know, at last, the true spirit of humanity.