WSJ Historically Speaking: Women Who Led the Fight for Independence

In years to come, the 2014 Scottish independence campaign is likely to be remembered for its overflowing testosterone. In this case, it was men brandishing their microphones. The campaign leaders, the debaters, the pollsters, even the egg-throwers were predominantly male. Women’s voices seemed to form a polite backdrop, as though the entire country had suffered a fit of 19th-century female gentility—except for the fact that actual 19th-century women were hardly shy about firing a rifle for independence.

The 1820s and ’30s in particular were a vintage time for the female independentista. Across the globe, from the Spanish-American Wars of Independence to the Greek Revolution to the November Uprising in the Polish-Russian War, women became spies, nurses, soldiers, couriers, sutlers, propagandists and even unofficial bankers. Some lived to tell the tale; some didn’t.

So many women helped Gen. José de San Martín to liberate Peru from Spain in 1821 that more than a hundred were nominated to receive the honorific Order of the Sun. Among them was the beautiful Manuela Sáenz (1797-1856), a pistol-firing, cigar-smoking heroine who found that the experience only whetted her appetite for more action. In 1822, when the great liberator Simón Bolívar rode past her balcony, Sáenz is said to have caught his attention by throwing flowers into his lap. At a reception that night, he purportedly quipped, “If all my soldiers had your aim, I would have won all the battles.”

So began one of the great love affairs of all time. Unfortunately, the attention Sáenz received as Bolívar’s lover has often overshadowed her physical bravery on the field, not to mention her prowess as a politician and military strategist.

After Bolívar’s death in 1830, a campaign of vilification led Sáenz to internal exile in Paita, a one-horse town in Peru. The novelist Herman Melville visited in 1841, telling her, “I admire you, not as the victor crowned by honors, but as the defeated.” Many Peruvians took rather a different view. She died a pauper and was all but forgotten until the mid-20th century. Sáenz’s rehabilitation was assured when the Chilean Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda composed an elegy to her in 1962: “Goodbye, Manuela Sáenz, pure smuggler / guerrilla. Perhaps your love has compensated / the parched loneliness and the empty night.”

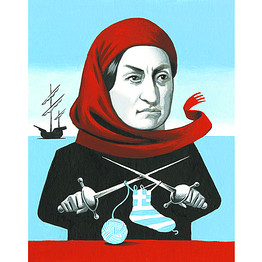

Many of the women who fought for Greek independence fared no better than their Latina sisters. The naval commander Adm. Laskarina Bouboulina, for example, was killed during a family feud in 1825.

The doomed women of the Siege of Missolonghi suffered even more. Lord Byron had died in the western Greek town of Missolonghi in 1824. Two years later, its position had become hopeless. The inhabitants decided to make a last-ditch attack against their Ottoman besiegers. Almost everyone joined the charge, including women with babies strapped to their backs. Only a handful of women made it out alive. The rest were killed, enslaved or blew themselves up in a mass suicide. The Greek playwright Evanthia Kairi (1799-1866) dedicated her tragedy “Nikiratos” to the “women sacrificed for Greece.”

In Poland, Countess Emilia Plater (1806-31) became a national heroine after she died while trying to break through to Warsaw. She was immortalized in countless paintings, poems and books. In the 1930s, Plater adorned the 20 zloty note. During World War II, a military unit bore her name. She even has a clematis vine, the purple C. Emilia Plater, named after her.

In short, pace the Scots: There’s more to being a brave heart than wearing a kilt.