WSJ Historically Speaking: A Hairy Issue: Beards Through History

There is a reason you may be seeing more beards these days on TV or the street. It has nothing to do with a resurgence of Victorian aesthetics, a mass outbreak of folliculitis or the conquest of the U.S. by hipsters.

The embrace of cheek-fuzz is actually part of a world-wide hair-a-thon to raise money for cancer charities. No-Shave November and its Australian-born cousin, Movember, are annual events that invite participants to forswear their razors for a month. The point, as the No-Shave November website puts it, is “to grow awareness by embracing our hair, which many cancer patients lose, and letting it grow wild and free.”

Those of us who associate beards with Santa Claus and Gandalf the Grey from “The Hobbit” movies can thank Movember for the useful reminder that the fur factor has always been a serious issue for men. Archaeologists have found 100,000 year-old cave drawings purportedly depicting beardless figures, which suggests that some of our Homo sapiens ancestors may have preferred the clean-shaven look. Ancient detritus reveals that seashells were used to pluck out hairs, anticipating the practice of electrolysis, only without the benefit of modern pain relief. Since the average beard has been estimated to contain some 15,500 whiskers, carefully removing each one would have required the utmost endurance.

According to the makers of Gillette, the first razors were invented perhaps 30,000 years ago. These were flint blades that, like their modern equivalents, could be discarded once they grew dull. They remained the shaving tool of choice until the Egyptians honed the copper razor around 3000 B.C. For a while, Egyptian fashion ran to extreme depilation from head to foot. The pharaohs sported false beards made of gold and silver, which they tied behind their ears with ribbons. Queen Hatshepsut proudly wore hers in a spectacular braid, making her the original bearded lady. (No rival would claim that title until St. Wilgefortis, a young, 14th-century noblewoman, allegedly grew a beard to avoid marriage. She’s often claimed as an unofficial patron saint of unhappily married women.)

Ironically, the transition to the sturdier iron razor coincided with a global free-for-all when it came to the cheek and the jowl. The Greeks preferred the bearded look; the Romans went for the smooth. The Persians dyed their beards red, while the Britannic tribes opted for the Charlie Chaplin mustache (or the John Galliano, if they were feeling unpredictable).

No consensus on men’s personal grooming emerged until the Enlightenment, when an “open countenance” became synonymous with an open or inquiring mind. Determined to haul Russia out of the Dark Ages, Peter the Great shocked his nobles by ordering the men to shave and the women to learn to read. By the end of the 18th century, only the mad, bad and dangerous-to-know went hirsute. In “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” Samuel Taylor Coleridge signals that horror and dread are afoot long before the arrival of the albatross. The very first verse describes the mariner with a “long grey beard and glittering eye.” If that weren’t enough, he is called a “grey-beard loon” in the third.

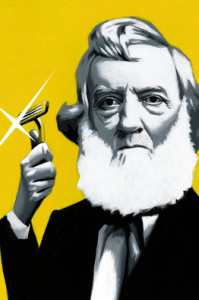

The Victorians, on the other hand, rejected everything their grandparents stood for in the barbate department and turned the beard into yet another race for global domination. The Americans won by inches, as anyone will attest after comparing Charles Darwin’s beard with that of, say, Gideon Welles, Lincoln’s impressively hairy secretary of the Navy. But by the time Rutherford B. Hayes claimed the prize for the longest beard in presidential history, the fashion for pogonophilia was running its course.

Today, except for certain neighborhoods of Brooklyn, the mutton chop, the chin curtain and the full ZZ Top have become as rare as a VHS tape. With November drawing to a close, the adage once again comes to the fore: hair today, gone tomorrow.