Employees are starting to return to their traditional desks in large shared spaces. But centuries ago, ‘office’ just meant work to be done, not where to do it.

June 24, 2021

Wall Street wants its workforce back in the office. Bank of America, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have all let employees know that the time is approaching to exchange pajamas and sweats for less comfortable work garb. Some employees are thrilled at the prospect, but others waved goodbye to the water cooler last year and have no wish to return.

Contrary to popular belief, office work is not a beastly invention of the capitalist system. As far back as 3000 B.C, the temple cities of Mesopotamia employed teams of scribes to keep records of official business. The word “office” is an amalgamation of the Latin officium, which meant a position or duty, and ob ficium, literally “toward doing.” Geoffrey Chaucer was the first writer known to use “office” to mean an actual place, in “The Canterbury Tales” in 1395.

In the 16th century, the Medicis of Florence built the Uffizi, now famous as a museum, for conducting their commercial and political business (the name means “offices” in Italian). The idea didn’t catch on in Europe, however, until the British began to flex their muscles across the globe. When the Royal Navy outgrew its cramped headquarters, it commissioned a U-shaped building in central London originally known as Ripley Block and later as the Old Admiralty building. Completed in 1726, it is credited with being the U.K.’s first purpose-built office.

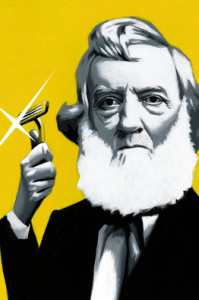

Three years later, the East India Company began administering its Indian possessions from gleaming new offices in Leadenhall Street. The essayist and critic Charles Lamb joined the East India Company there as a junior clerk in 1792 and stayed until his retirement, but he detested office life, calling it “daylight servitude.” “I always arrive late at the office,” he famously wrote, “but I make up for it by leaving early.”

A scene from “The Office,” which reflected the modern ambivalence toward deskbound work.

PHOTO: CHRIS HASTON/NBC/EVERETT COLLECTION

Not everyone regarded the office as a prison without bars. For women it could be liberating. An acute manpower shortage during the Civil War led Francis Elias Spinner, the U.S. Treasurer, to hire the government’s first women office clerks. Some Americans were scandalized by the development. In 1864, Rep. James H Brooks told a spellbound House that the Treasury Department was being defiled by “orgies and bacchanals.”

In the late 19th century, the inventions of the light bulb and elevator were as transformative for the office as the telephone and typewriter: More employees could be crammed into larger spaces for longer hours. Then in 1911, Frederick Winslow Taylor published “The Principles of Scientific Management,” which advocated a factory-style approach to the workplace with rows of desks lined up in an open-plan room. “Taylorism” inspired an entire discipline devoted to squeezing more productivity from employees.

Sinclair Lewis’s 1917 novel, “The Job,” portrayed the office as a place of opportunity for his female protagonist, but he was an outlier among writers and social critics. Most fretted about the effects of office work on the souls of employees. In 1955, Sloan Wilson’s “The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit,” about a disillusioned war veteran trapped in a job that he hates, perfectly captured the deep-seated American ambivalence toward the office. Modern television satires like “The Office” show that the ambivalence has endured—as do our conflicted attitudes toward a post-pandemic return to office routines.