The Sunday Times: Modern authoritarians aren’t out to kill freedom, merely cripple it

In 1984 the French intellectual, Jean-François Revel, now deceased, published How Democracies Perish, in which he predicted: “Democracy may, after all, turn out to have been a historical accident, a brief parenthesis that is closing before

our eyes.”

Less than a decade later, spurred by the fall of the Berlin Wall, he appeared to take the opposite view in Democracy Against Itself, claiming: “Democracy is not only conceivable, it is inevitable. It has been indispensable, but until now it was not inevitable.”

Not surprisingly, Revel, a staunch supporter of America’s battle against the Soviet Union, was ridiculed by critics for his inconsistency.

I didn’t give much thought to Revel after that; at least, not until this year when I began my trek across the world on behalf of the BBC. Then I couldn’t get him out of my mind. I began to see for myself what life is like when there is no such thing as a Bill of Rights, or separation between church and state, or between state and party.

It’s not that I witnessed some terrible act of violence. There was no single incident that will remain seared in my memory. It was more like watching the death of freedom by a thousand cuts. There are so many ways it can be done, many of them hardly noticeable at first.

Some countries still resort to the blunt instrument, of course. When we filmed in Vietnam the crew were assigned two official minders, one to watch us and one to watch the watcher.

They got so bored during the long days of filming that to pass the time they took to helping with the equipment. But it didn’t matter how many tripods or lights they carried, they were basically spies and we were their marks, with all that entailed.

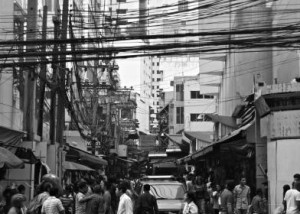

Most of the time the constraints on freedom that I encountered were of the institutional kind in countries where corruption is a form of government, where access to the internet is tightly controlled and where simply getting on with business is subject to permission.

On a practical level, in China for example, that didn’t just mean being cut off from Twitter, Google, YouTube, Dropbox, Facebook and Instagram, it also meant being prevented from accessing any research or book that wasn’t sanctioned by the government.

In Turkey it meant filming at the mercy of official whim that at times bordered on harassment. In Russia it meant trying to operate under a cloud of unpredictability.

In all the countries I filmed in where freedom is a relative concept, the common denominator was a cowed press and an opaque economy. The Freedom in the World report for 2014, published by the US-based Freedom House organisation, put the problem neatly. It warned that the greatest threats to freedom stem from the spread of “modern authoritarianism”. Today’s authoritarians are using the mechanisms of soft power to maintain the veneer of freedom while undermining it all the while.

Modern authoritarianism isn’t interested in destroying all dissent, merely in crippling it. Whether it’s China, Russia or Turkey, or Venezuela, Zimbabwe or Iran, what separates the modern authoritarians from genuinely democratic countries is their successful co-opting of the institutions that support society: the judiciary, the media, the internet, the economy, the security forces and both the legislative and executive branches of government.

In other words, the easiest way to subvert freedom, pluralism and democracy is to attack it from the inside. Many of the American founding fathers were aware that even a written constitution was not in itself a sufficient bulwark against federal overreach. That was why the original 10 amendments in the Bill of Rights, from freedom of speech to the guarantee of states’ rights, were first ratified in 1791.

The Bill of Rights presents a robust rampart against the kind of assaults on liberty that have become typical in places such as Turkey, where another 23 journalists and editors were arrested this month on terrorism charges. But there are other, more subtle — although no less dangerous — threats to democracy that the bill is not equipped to repulse.

For America in 2015 these threats include the rise of untouchable hegemonies in the corporate world, the growing intolerance of dissent in the social, and the increasingly heavy hand of security wielded by the state.

It has been 30 years since the last great monopoly, the AT&T corporation, was parcelled up by the government into smaller companies. AT&T owned the entire telephone system, as well as being the sole relay and cable provider for network TV and radio. Its break-up unleashed the power of communication from the mobile to the net.

But since then a host of new companies have carved out monopolies and near-monopolies that impinge on American life, from the tech giants to the domination of the consumer market by a few retailers such as Walmart. Together they create the illusion of choice, freedom and fairness, but without competition and regulation it is just that — an illusion.

As for social orthodoxy, from the forced resignation of the chief executive of Mozilla, the creator of the web browser Firefox, for not being in favour of gay marriage, to the campus hounding of the women’s rights activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali for her insensitivity towards Islam, 2014 was a bad year for freedom of conscience.

Finally, there is the growing challenge to civil liberties in the name of safety. In November the Legatum Institute published its annual prosperity index: it showed that the United States had slipped badly in the world rankings for personal freedom from 9th to 21st place.

No country is more committed to upholding personal liberty than America. But the exposure of super-surveillance by the security agencies, the snaring of political journalists by the Espionage Act and the growing number of deadly police incidents against African-American men have impoverished civil society.

What I learnt this year is that we must be the guardians of democracy: it is fragile and will not survive without constant vigilance.