WSJ Historically Speaking: Postal Pitfalls, From Beacons to Emails

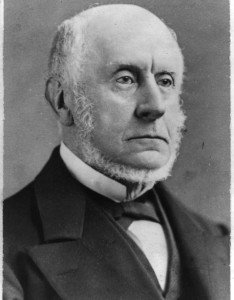

Charles Francis Adams was an American historical editor, politician and diplomat. He was the son of President John Quincy Adams and grandson of President John Adams, of whom he wrote a major biography. PHOTO: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

It’s now 150 years since a trans-Atlantic cable finally crackled into continuous action after nine years of false starts and disappointments. The transmission speed of up to eight words a minute seemed to the Victorians almost godlike. Small wonder that the first telegram in the U.S., sent about two decades earlier, had read, “What hath God wrought.”

Our desire for instantaneous dialogue is as old as language itself. Contemporaries praised the masterful use of rapid communication by Persian King Xerxes I, who ruled from 486 to 465 B.C. and was famous for having slaughtered the Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Xerxes’ messengers were the best in the ancient world, for “neither snow nor rain nor heat nor night holds back for the accomplishment of the course.” That sentiment, translated a bit differently, ended up chiseled in stone above the front columns of the New York City Post Office on Eighth Avenue.

The Chinese also recognized the need for speed. When it came to defending China’s vast border, successive dynasties relied more on the swiftness of their fire beacons than on the strength of the Great Wall. The great Chinese historian Sima Qian, who died in 86 B.C., blamed the fall of the Western Zhou Dynasty on King You of Zhou (795-771 B.C.). According to the historian, You trifled with the country’s early warning system, triggering it and rousing his allies, just to make his concubine laugh.

As anyone who has ever embarrassed himself by dashing off a hasty email can attest, speed can be a double-edged sword. During the so-called Trent Affair of 1861, it may have been mere luck, provided by the broken trans-Atlantic cable, that prevented America and Britain from going to war for a third time.

The row was provoked by Capt. Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Navy. He stopped a neutral British ship on the high seas and, on board at gunpoint, seized two Confederate diplomats who were on a mission to Europe to secure international recognition of the Confederacy. If the cable had still been working, there would have been no means of slowing down the barrage of tit-for-tat messages between the two capitals.

Instead, the two governments sent angry missives to each other. Fortunately, each letter took two weeks to arrive. The time in between provided sufficient leeway for the countries’ ambassadors, Lord Lyons in Washington and Charles Francis Adams in London, to work out a form of compromise so that both nations could emerge from the debacle with their honor intact.

The most famous think-before-you-send example is the Zimmermann Telegram incident of World War I. Desperate to get Mexico to join the war on Germany’s side (in return for help against the U.S.), German foreign secretary Arthur Zimmermann rashly decided in 1917 to send a proposal of alliance via coded telegram.

The only way to get it to the Mexicans quickly, however, was to use the trans-Atlantic cable and have the message relayed by the U.S. State Department down to Mexico. Using the facilities of a host country to conspire against it is one thing; assuming that telegrams, like emails, are 100% safe and can’t be read by anyone else is another. The British broke the German code and revealed its contents. The telegram was one of the main catalysts for America’s April 1917 entry into the war on the side of the Allies.

Of course, those speedy communications pale next to our current message system. It passed a milestone of its own on Saturday with the death of computer programmer Ray Tomlinson, who is considered to have invented the email of today, including the ubiquitous “at” sign. Our network’s speed—and capacity for error—makes the moral of these tales of messaging pitfalls all the more important. Caesar Augustus (63 B.C.-A.D. 14) said it best to his Roman generals: “Festina lente,” which means, “Make haste slowly.”