WSJ Historically Speaking: Resolved to Lose Weight in ’16? Join a Venerable Club

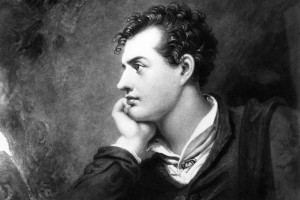

English Romantic poet George Gordon Noel Byron (from around 1810). To keep his weight down, he subsisted on a diet of flattened potatoes drenched in vinegar. PHOTO: HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

Resolutions and Jan. 1 have a fatal attraction for one another—much like beer and pizza. The vow most often cited, “to go on a diet,” also happens to be the one most quickly abandoned. According to a 2013 British study, two out of five dieters don’t make it beyond the first week.

The problem isn’t that people are lazy or spoiled. It’s that the purpose of a diet has become divorced from its original intentions. The ancient Greeks were largely responsible for the concept. “Diatia” means “way of life” or “regimen.” How a person approached the business of eating was as important as what entered his stomach. Balance, self-control and proper order were thought to be three key aspects to living the good life. Only barbarians, such as the Persians, gorged on luxuries.

The two greatest doctors of the classical world, Hippocrates (around 460 to 375 B.C.) and Galen (A.D. 129 to about 216) had strong ideas about the kind of diatia everyone should follow. They argued that the mind and body were controlled by four humors: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. The goal was to keep them in equilibrium. A surplus of phlegm, for example, could make a patient lethargic, requiring more citrus in the diet. Too much black bile, on the other hand, made a person melancholic—which, Galen thought, required bloodletting or purging to remove the noxious humors from the body.

The early Christian ascetics overthrew the classical concept of the good diet. Their obsession with purity and fasting turned the body into another battleground in the war between good and evil. Food was seen as the devil’s ammunition, since it was tainted by earthly corruption (and, worse, was a vehicle for pleasure). The logical extreme of such religious asceticism was death by starvation, a “success” achieved by a number of saints, including St. Catherine of Siena (1347-1380), whose mortification of the flesh included drinking the pus of an infected patient.

By the 18th century the association of goodness with thinness had become a fact of life. As Jane Austen (1775-1817) ruefully admitted in the novel “Persuasion,” it was difficult to take a fat person seriously: “fair or not fair, there are unbecoming conjunctions…which taste cannot tolerate,—which ridicule will seize.” Perhaps that is why Lord Byron (1788-1824), who took himself exceptionally seriously, became so obsessed with being skinny. His gift to culture—apart from his writing—was an extremely unpleasant diet of flattened potatoes drenched in vinegar. Byron quenched the inevitable hunger pangs that followed with a diet of cigars. He single-handedly popularized the pale and scrawny look so ubiquitous among devotees of romanticism.

Byron unleashed 200 years of diet quackery. The 19th century was not without sensible writers like William Banting (1797-1878) who recognized the dangers of rich and sugary food. But it’s been the charlatans and their snake-oil remedies—from Prolinn (a disgusting 1970s concoction) to blue-tinted glasses (an alleged appetite suppressant)—that have proliferated in the 20th century.

Yet it’s never too late to return to the first principles behind diatia. As Hesiod, the 8th-century B.C. poet, said: “Moderation is best in all things.”