WSJ Historically Speaking: The Second Life of Troubled Inventions

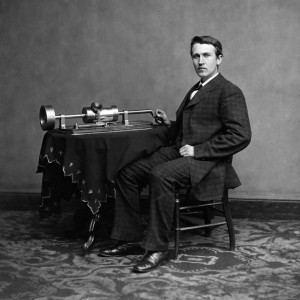

Thomas Edison, circa 1870s, with his phonograph PHOTO: EVERETT COLLECTION

It’s been a difficult time for the high-profile medical startup Theranos. For months, controversies have shadowed the linchpin Edison blood-testing device that the Palo Alto, Calif., company has developed. The method uses a few drops of blood, obtained by a finger-stick, instead of the usual multiple vials.

The fate of the Edison device, named after the inventor, remains unclear. But the story of Thomas Edison himself offers some hope. Not all troubled products remain troubled.

In 1875, the 28-year-old Edison had already obtained almost 100 patents without having invented something truly new. He thought he had the answer in the electric pen. Edison wanted to take the tedium out of copy-making by designing a motorized stylus that would act like a kind of stencil, able to punch words through a stack of papers up to 100 pages thick.

Edison was convinced he had created a winner, writing, “There is more money in this than telegraphy.” Sales started off strongly until customers began to complain that the pen was messy and almost impossible to wield. One unhappy user likened the experience to holding a wasp.

Edison moved on to his next idea, the phonograph, and sold his patent for the electric pen to a company that used a similar technology to create the mimeograph machine—which would feature in every teacher’s arsenal of tricks until Xerox came along with a better copier. Though discarded, the electric pen was by no means finished. It would eventually enjoy a second life in the 1890s as the first electric tattoo needle.

Around that time, inventors and tinkerers were locked in an international competition to build the first truly efficient carpet cleaner. Ever since the invention of the original mechanical carpet brush in 1860, every new cleaning device had the problem that it simply moved the dust around.

In 1898, John S. Thurman of St. Louis believed he had solved the issue with the invention of a gasoline-powered cleaner that had a canvas bag attached for catching the dust as it was blown into the air. Three years later, the demonstration of a prototype at the Empire Music Hall in London proved to be a disaster. Clouds of dust caused the audience to burst into fits of coughing and sneezes.

Among those in attendance, however, was a British engineer named Hubert Cecil Booth, who realized that a sucking rather than a blowing mechanism would do the trick. A year later, Booth began selling the first vacuum cleaner. But Thurman’s ingenuity was not in vain. The principle behind his “pneumatic carpet renovator” would go on to power that favorite of American suburban life: the leaf blower.

About 70 years later, a chemist at Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co., now 3M, was trying to create an extra-strong glue for the aerospace industry. To Spencer Silver’s intense frustration, his efforts resulted in an adhesive that barely stuck at all. The “invention” was shelved as just another failure, until a colleague wondered whether the nonstick glue could stop the bookmarks from falling out of his hymnbook. Thus the Post-It Note was born.

Somewhere, deep in the files of Theranos, there may yet be the equivalent of a Post-It Note.