May 12, 2022

The Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., is 100 years old this month. The beloved national monument is no less perfect for having one slight flaw: The word “future” in the Second Inaugural Address was mistakenly carved as “Euture.” It is believed that the artist, Ernest C. Bairstow, accidentally picked up the “e” stencil instead of the “f.” He tried to fix it by filling in the bottom line, but the smudged outline is still visible.

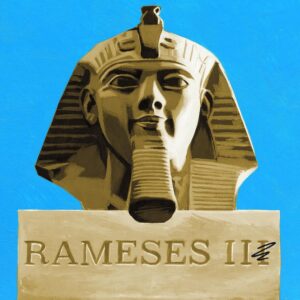

Bairstow was by no means the first engraver to rely on the power of fillers. It wasn’t uncommon for ancient Egyptian carvers—most of whom were illiterate—to botch their inscriptions. The seated Pharaoh statue at the Penn Museum in Philadelphia depicts Rameses II, third Pharaoh of the 19th dynasty, who lived during the 13th century BC. Part of the inscription ended up being carved backward, which the artist tried to hide with a bit of filler and paint. But time and wear have made the mistake, well, unmistakable.

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

Medieval scribes were notorious for botching their illuminated manuscripts, using all kinds of paint tricks to hide their errors. But for big mistakes—for example, when an entire line was dropped—the monks could get quite inventive. In a 13th-century Book of Hours at the Walters Museum in Baltimore, an English monk solved the problem of a missing sentence by writing it at the bottom of the page and drawing a ladder with man on it, pulling the sentence by a rope, to where it was meant to be.

The phrase “the devil is in the details” may have been inspired by Titivillus, the medieval demon of typos. Monks were warned that Titivillus ensured that every scribal mistake was collected and logged, so that it could be held against the offender at Judgment Day.

The warning seems to have had only limited effect. The English poet Geoffrey Chaucer was so enraged by his copyist Adam Pinkhurst that he attacked him in verse, complaining he had “to rub and scrape: and all is through thy negligence and rape.”

The move to print failed to solve the problem of typos. When Shakespeare’s Cymbeline was first committed to text, the name of the heroine was accidentally changed from Innogen to Imogen, which is how she is known today. Little typos could have big consequences, such as the so-called Wicked Bible of 1631, whose printers managed to leave out the “not” in the seventh commandment, thereby telling Christians that “thou shalt commit adultery.”

The rise of the newspaper deadline in the 19th century inevitably led to typos big and small, as well as those unfortunate and unlikely. In 1838, British readers of the Manchester Guardian were informed that “writers” rather than “rioters” had caused extensive property damage during a protest meeting in Yorkshire.

In the age of computers, a single typo can have catastrophic consequences. On July 22, 1962, NASA’s Mariner 1 probe to Venus exploded just 293 seconds after launching. The failure was traced to an inputting error. A single hyphen was inadvertently left off one of the codes.