Body ink has been used to elevate, humiliate and decorate people since the times of mummies.

August 25, 2022

Earlier this month the celebrity couple Kim Kardashian and Pete Davidson announced that their nine-month relationship was over. Ms. Kardashian departed with her memories, but Mr. Davidson was left with something a little more tangible: the words “my girl is a lawyer” tattooed on his shoulder in (premature) homage to Ms. Kardashian’s legal aspirations. He has since been inundated on social media with suggestions on how to cover it up. In 1993, following his split with actress Winona Ryder, the actor Johnny Depp changed “Winona Forever” to “Wino Forever.”

Throughout history, humans have tattooed themselves—and others—for reasons spanning the gamut from religion to revenge. The earliest evidence for tattooing comes from a 5,300-year-old ice mummy nicknamed Otzi after its discovery in the Ötztal Alps in Europe. An analysis of Otzi’s remains revealed that he had been killed by an arrow. Even before his violent death, however, he appeared to have suffered from various painful ailments. Scientists found 61 tattoo marks across Otzi’s body, with many of them placed on known acupuncture points, prompting speculation that the world’s oldest tattoos were used as a health aid.

Similar purposes may have prompted the ancient Nubians to apply tattoos on some pregnant women. Tomb paintings and mummified remains of women in Egypt show that they also adopted the custom, possibly for the same reason.

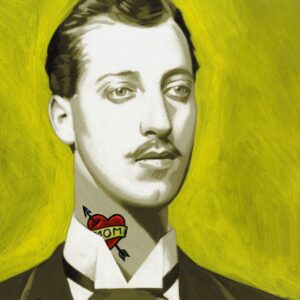

PHOTO: THOMAS FUCHS

The indelible aspect of tattooing inspired diametrically opposed attitudes. Some ancient peoples, such as the Thracians and the Gauls, regarded tattoos as a mark of noble status and spiritual power. But the Persians, Greeks and Romans used them as a form of punishment or humiliation. Those who imported slaves to Rome from Asia paid duties and tattooed “tax paid” on the foreheads of those they enslaved.

In Polynesian cultures, tattoos were imbued with symbolism. The traditional tatau, which gave rise to the English word tattoo via Captain James Cook in the 18th century, covered the bodies of Samoan men from the waist to the knees. The ritual application took many weeks and entailed excruciating pain plus the danger of septicemia, but anyone who gave up brought shame upon his family for generations.

As a rule, Christian missionaries tried to stamp out the practice during the 19th century. But their disapproval was no match for royal enthusiasm. Fascinated by irezumi, the Japanese decorative art of tattooing inspired by woodblock printing, the future King George V of Britain and his brother Prince Albert Victor both had themselves inked in 1881 while on a royal visit. Noting its subsequent spread among the American upper classes, the New York Herald complained, “The Tattooing Fad has Reached New York Via London.”

In the 20th century, the practice retained a dark side as a symbol of criminality and oppression—most notably associated with the Nazis’ tattooing of inmates at Auschwitz. At the same time, however, so many returning U.S. servicemen had them that the Marlboro Man sported one on his hand in the advertisements of the day.