From the Warsaw Ghetto to the Alamo, doomed rebels live on in culture

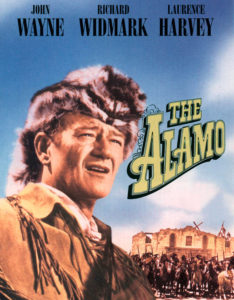

John Wayne said that he saw the Alamo as ‘a metaphor for America’. PHOTO: ALAMY

Earlier this month, Israel commemorated the 75th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April 1943. The annual Remembrance Day of the Holocaust and Heroism, as it is called, reminds Israelis of the moral duty to fight to the last.

The Warsaw ghetto battle is one of many doomed uprisings across history that have cast their influence far beyond their failures, providing inspiration to a nation’s politics and culture.

Nearly 500,000 Polish Jews once lived in the ghetto. By January 1943, the Nazis had marked the surviving 55,000 for deportation. The Jewish Fighting Organization had just one machine gun and fewer than a hundred revolvers for a thousand or so sick and starving volunteer soldiers. The Jews started by blowing up some tanks and fought on until May 16. The Germans executed 7,000 survivors and deported the rest.

Other doomed uprisings have also been preserved in art. The 48-hour Paris Uprising of 1832, fought by 3,000 insurrectionists against 30,000 regular troops, gained immortality through Victor Hugo, who made the revolt a major plot point in “Les Misérables” (1862). The novel was a hit on its debut and ever after—and gave its world-wide readership a set of martyrs to emulate.

Even a young country like the U.S. has its share of national myths, of desperate last stands serving as touchstones for American identity. One has been the Battle of the Alamo in 1836 during the War of Texas Independence. “Remember the Alamo” became the Texan war cry only weeks after roughly 200 ill-equipped rebels, among them the frontiersman Davy Crockett, were killed defending the Alamo mission in San Antonio against some 2,000 Mexican troops.

The Alamo’s imagery of patriotic sacrifice became popular in novels and paintings but really took off during the film era, beginning in 1915 with the D.W. Griffith production, “Martyrs of the Alamo.” Walt Disney got in on the act with his 1950s TV miniseries, “ Davy Crockett : King of the Wild Frontier.” John Wayne’s 1960 “The Alamo,” starring Wayne as Crockett, immortalized the character for a generation.

Wayne said that he saw the Alamo as “a metaphor of America” and its will for freedom. Others did too, even in very different contexts. During the Vietnam War, President Lyndon Johnson, whose hometown wasn’t far from San Antonio, once told the National Security Council why he believed U.S. troops needed to be fighting in Southeast Asia: “Hell,” he said, “Vietnam is just like the Alamo.”