A mosquito-borne parasite has impoverished nations and stopped armies in their tracks

October 15, 2021

Last week brought very welcome news from the World Health Organization, which approved the first-ever childhood vaccine for malaria, a disease that has been one of nature’s grim reapers for millennia.

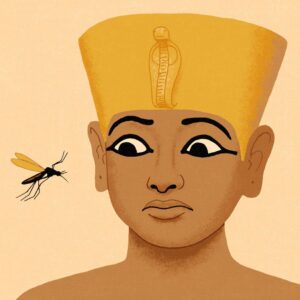

Originating in Africa, the mosquito-borne parasitic infection left its mark on nearly every ancient society, contributing to the collapse of Bronze-Age civilizations in Greece, Mesopotamia and Egypt. The boy pharaoh Tutankhamen, who died around 1324 BC, suffered from a host of conditions including a club foot and cleft palate, but malaria was likely what killed him.

Malaria could stop an army in its tracks. In 413 BC, at the height of the disastrous Sicilian Expedition, malaria sucked the life out of the Athenian army as it lay siege to Syracuse. Athens never recovered from its losses and fell to the Spartans in 404 BC.

But while malaria helped to destroy the Athenians, it provided the Roman Republic with a natural barrier against invaders. The infested Pontine Marshes south of Rome enabled successive generations of Romans to conquer North Africa, the Middle East and Europe with some assurance they wouldn’t lose their own homeland. Thus, the spread of classical civilization was carried on the wings of the mosquito. In the 5th century, though, the blessing became a curse as the disease robbed the Roman Empire of its manpower.

Throughout the medieval era, malaria checked the territorial ambitions of kings and emperors. The greatest beneficiary was Africa, where endemic malaria was deadly to would-be colonizers. The conquistadors suffered no such handicap in the New World.

ILLUSTRATION: JAMES STEINBERG

The first medical breakthrough came in 1623 after malaria killed Pope Gregory XV and at least six of the cardinals who gathered to elect his successor. Urged on by this catastrophe to find a cure, Jesuit missionaries in Peru realized that the indigenous Quechua people successfully treated fevers with the bark of the cinchona tree. This led to the invention of quinine, which kills malarial parasites.

For a time, quinine was as powerful as gunpowder. George Washington secured almost all the available supplies of it for his Continental Army during the War of Independence. When Lord Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown in 1781, less than half his army was fit to fight: Malaria had incapacitated the rest.

During the 19th century, quinine helped to turn Africa, India and Southeast Asia into a constellation of European colonies. It also fueled the growth of global trade. Malaria had defeated all attempts to build the Panama Canal until a combination of quinine and better mosquito control methods led to its completion in 1914. But the drug had its limits, as both Allied and Axis forces discovered in the two World Wars. While fighting in the Pacific Theatre in 1943, General Douglas MacArthur reckoned that for every fighting division at his disposal, two were laid low by malaria.

A raging infection rate during the Vietnam War was malaria’s parting gift to the U.S. in the waning years of the 20th century. Between 1964 and 1973, the U.S. Army suffered an estimated 391,965 sick-days from malaria cases alone. The disease didn’t decide the war, but it stacked the odds.

Throughout history, malaria hasn’t had to wipe out entire populations to be devastating. It has left them poor and enfeebled instead. With the advent of the new vaccine, the hardest hit countries can envisage a future no longer shaped by the disease.