Caustic comebacks have been exchanged between military leaders for millennia, from the Spartans to World War II

August 6, 2020

In the center of Bastogne, Belgium (pop. 16,000), there is a statue of U.S. Army General Anthony C. McAuliffe, who died 45 years ago this week. It’s a small town with a big history. Bastogne came under attack during the final German offensive of World War II, known as the Battle of the Bulge. The town was the gateway to Antwerp, a vital port for the Allies, and all that stood between the Germans and their objective was Gen. McAuliffe and his 101st Airborne Division. Despite being outnumbered by a factor of four to one, he refused to surrender, fighting on until Gen. George Patton’s reinforcements could break the siege.

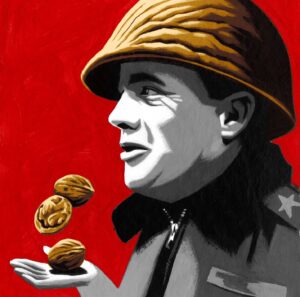

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

While staving off the German attack, Gen. McAuliffe uttered the greatest comeback of the war. A typewritten ultimatum from Commander Heinrich von Lüttwitz of the 47th German Panzer Corps gave him two hours to surrender the town or face “annihilation.” With ammunition running low and casualties mounting, the general made his choice. He sent back the following typed reply:

December 22, 1944

To the German Commander,

N U T S !

The American Commander

The true laconic riposte is extremely rare. The Spartans, whose ancient homeland of Lakonia inspired the term “laconic,” were masters of the art. When Philip II of Macedon ordered them to open their borders, he warned them, “For if I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people and raze your city.” According to the later account of the Greek philosopher Plutarch, they sent back a one-word message: ‘If’.

Once the age of the Spartans passed, it took more than a millennium for the laconic comeback to return in earnest. The man most responsible was a colorful Teutonic knight called Götz von Berlichingen, who participated in countless German conflicts, uprisings and skirmishes, including the Swabian War between the Hapsburgs and the Swiss. He lost a hand to a cannonball and wore an iron prosthesis (hence his nickname, Götz of the Iron Hand). In 1515, sick of trading insults with an opponent who wouldn’t come out to fight, Götz abruptly ended the conversation with: “soldt mich hinden leckhenn,” which literally meant “kiss my ass.”

He recorded the encounter in his memoirs, but it remained little known until Johann Wolfgang von Goethe adapted Götz’s autobiography into a successful play in 1773. From then on, the insult was popularly known in Germany as a “Swabian salute.”

In his novel “Les Misérables,” Victor Hugo—possibly inspired by Goethe—immortalized the French defeat in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo with a scene of spectacular, if laconic, defiance that incorporated France’s most common expletive. According to Hugo, Gen. Pierre Cambronne, commander of Napoleon Bonaparte’s Imperial Guard, fought to the last syllable in the face of overwhelming force. Encircled by the British army, “They could hear the sound of the guns being reloaded and see the lighted slow matches gleaming like the eyes of tigers in the dusk. An English general called out to them, ‘Brave Frenchmen, will you not surrender?’ Cambronne answered, ‘Merde’” (that is, “shit”).

The scene’s veracity is still hotly debated, the fog of war making memories hazy. But Cambronne—who survived—later disavowed it, especially after “le mot de Cambronne’’ (Cambronne’s word) became a common euphemism for the profanity.