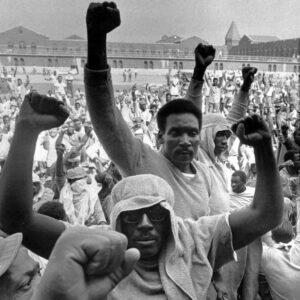

Fifty years ago, the Attica uprising laid bare the conflicting ideas at the heart of the U.S. prison system.

September 17, 2021

Nearly two centuries earlier, the founders of the U.S. penal system had intended it as a humane alternative to those that relied on such physical punishments as mutilation and whipping. After the War of Independence, Benjamin Franklin and leading members of Philadelphia’s Quaker community argued that prison should be a place of correction and penitence. Their vision was behind the construction of the country’s first “penitentiary house” at the Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia in 1790. The old facility threw all prisoners together; its new addition contained individual cells meant to prevent moral contagion and to encourage prisoners to spend time reflecting on their crimes.

Inmates protest prison conditions in Attica, New York, Sept. 10, 1971

Walnut Street inspired the construction of the first purpose-built prison, Eastern State Penitentiary, which opened outside of Philadelphia in 1829. Prisoners were kept in solitary confinement and slept, worked and ate in their cells—a model that became known as the Pennsylvania system. Neighboring New York adopted the Auburn system, which also enforced total silence but required prisoners to work in communal workshops and instilled discipline through surveillance, humiliation and corporal punishment. Although both systems were designed to prevent recidivism, the former stressed prisoner reform while the latter carried more than a hint of retribution.

Europeans were fascinated to see which system worked best. In 1831, the French government sent Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont to investigate. Having inspected facilities in several states, they concluded that although the “penitentiary system in America is severe,” its combination of isolation and work offered hope of rehabilitation. But the novelist Charles Dickens reached the opposite conclusion. After touring Eastern State Penitentiary in 1842, he wrote that the intentions behind solitary confinement were “kind, humane and meant for reformation.” In practice, however, total isolation was “worse than any torture of the body”: It broke rather than reformed people.

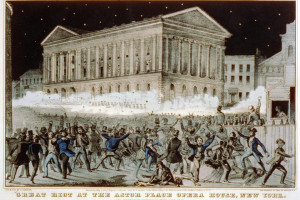

Severe overcrowding—there was no parole in the 19th century—eventually undermined both systems. Prisoner violence became endemic, and regimes of control grew harsher. Sing Sing prison in New York meted out 36,000 lashes in 1843 alone. In 1870, the National Congress on Penitentiary and Reformatory Discipline proposed reforms, including education and work-release initiatives. Despite such efforts, recidivism rates remained high, physical punishment remained the norm and almost 200 serious prison riots were recorded between 1855 and 1955.

That year, Harry Manuel Shulman, a deputy commissioner in New York City’s Department of Correction, wrote an essay arguing that the country’s early failure to decide on the purpose of prison had immobilized the system, leaving it “with one foot in the road of rehabilitation and the other in the road of punishment.” Which would it choose? Sixteen years later, Attica demonstrated the consequences of ignoring the question.