WSJ Historically Speaking: A Night at the Theater Often Used to Be a Riot

Before the era of sky-‐high ticket prices, the theater functioned much like a public park: a communal space where all social classes could come together. The drama onstage was often just a backdrop for the public theater being enacted by the audience. Political venting, social protesting and even rioting were common occurrences—especially in springtime, when the warmer weather let open-‐air theaters resume business.

The Nika riots in 6th-century Byzantium (so dubbed because the rioters chanted “Nika,” meaning “conquer” or “win”) remain the deadliest in theater history.

In 532 A.D., during the reign of Emperor Justinian, the two political factions—the aristocratic Blues and the plebeian Greens—unexpectedly united to protest against new taxes during a public spectacle at the Hippodrome. Using the storied arena as their base, the rioters managed to burn down more than half of Constantinople before Justinian had the Hippodrome surrounded and every exit blocked. His soldiers proceeded to slaughter everyone inside. Contemporary accounts claimed that the death toll exceeded 30,000. After that, public theater of any kind was strongly discouraged by the Byzantine authorities.

When theater revived during the Renaissance, so did audiences’ politicized behavior. By the 19th century, municipal authorities had become used to the odd disturbance after a performance. But on Aug. 25, 1830, the violent emotions aroused in Brussels—then under Dutch rule—by Daniel Auber’s “La Muette de Portici” (“The Mute Girl of Portici”) caught officials by surprise. The opera, loosely based on the Neapolitan uprising against the Spanish in 1647, had been performed before. But this time, the tenor singing the part of the peasant leader began to interpolate the “Marseillaise” into his aria. The Belgian audience shouted back as one and poured into the streets. Rioting against Dutch targets soon led to armed insurrection, and on Nov. 18, 1830, Belgium officially proclaimed its independence.

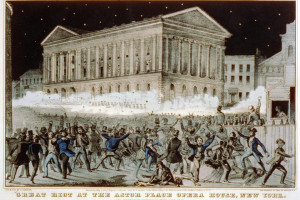

Nineteen years later, New Yorkers threatened to turn rival performances by two Shakespearean actors—the American Edwin Forrest and the British William Charles Macready—into a mini re-enactment of the War of Independence. Forrest was beloved by working-class audiences and supported by the Irish bosses of Tammany Hall; Macready was much admired by the city’s carriage trade and its Whig politicians. In May 1849, Forrest was booked to play “Macbeth” at the popular Broadway Theatre. A few blocks away, Macready was also set to perform “Macbeth” at the more exclusive Astor Place Theatre.

By 7:30 p.m. on May 10, a crowd of up to 10,000 had gathered outside Astor Place, nationalist and class tensions already deliberately inflamed by pro-Forrest posters that proclaimed, “Shall Americans or English rule this city?” Violence soon broke out both inside and outside the theater. It raged for some 20 hours, and Macready had to be smuggled out of the city in disguise. By the time peace was restored, at least 20 lay dead, and another 100 had been injured. The last victim of the Astor Place Riot was New York theater itself, which became Balkanized along class lines: opera and Shakespeare for the rich, music-hall and variety shows for the poor.

By the 20th century, the theater was no longer a melting pot of social tensions and desires. The much vaunted May 1913 riot during the Parisian opening night of Igor Stravinsky’s ballet “The Rites of Spring” was little more than a punch-up between rivals over artistic differences. The audience wasn’t fomenting revolution so much as experiencing one. The era when theater went hand-in-hand with public drama had passed.