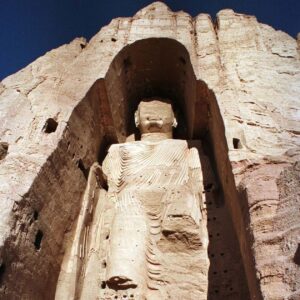

The 20th anniversary of the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan reminds us of the imperative of historical preservation

April 15, 2021

Twenty years ago this spring, the Taliban completed their obliteration of Afghanistan’s 1,500-year-old Buddhas of Bamiyan. The colossal stone sculptures had survived major assaults in the 17th and 18th centuries by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and the Persian king Nader Afshar. Lacking sufficient firepower, both gave up after partly defacing the monuments.

The Taliban’s methodical destruction recalled the calculated brutality of ancient days. By the time the Romans were finished with Carthage in 146 B.C., the entire city had been reduced to rubble. They were given a taste of their own medicine in 455 A.D. by Genseric, King of the Vandals, who stripped Rome bare in two weeks of systematic looting and destruction.

One of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in 1997, before their destruction.

PHOTO: ALAMY

Like other vanquished cities, Rome’s buildings became a source of free material. Emperor Constans II of Byzantium blithely stole the Pantheon’s copper roofing in the mid-17th century; a millennium later, Pope Urban VIII appropriated its bronze girders for Bernini’s baldacchino over the high altar in St. Peter’s Basilica.

When not dismantled, ancient buildings might be repurposed by new owners. Thus Hagia Sophia Cathedral became a mosque after the Ottomans captured Constantinople, and St. Radegund’s Priory was turned into Jesus College at Cambridge University on the orders of King Henry VIII.

The idea that a country’s ancient heritage forms part of its cultural identity took hold in the wake of the French Revolution. Incensed by the Jacobins’ pillaging of churches, Henri Gregoire, the Constitutional Bishop of Blois, coined the term vandalisme. His protest inspired the novelist Victor Hugo’s efforts to save Notre Dame. But the architect chosen for the restoration, Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, added his own touches to the building, including the central spire that fell when the cathedral’s roof burned in 2019, spurring controversy over what to restore. Viollet-le-Duc’s own interpolations set off a fierce debate, led by the English art critic John Ruskin, about what constitutes proper historical preservation.

Ruskin inspired people to rethink society’s relationship with the past. There was uproar in England in 1883 when the London and South Western Railway tried to justify building a rail-track alongside Stonehenge, claiming the ancient site was unused.

Public opinion in the U.S., when aroused, could be equally determined. The first preservation society was started in the 1850s by Ann Pamela Cunningham of South Carolina. Despite being disabled by a riding accident, Cunningham initiated a successful campaign to save George Washington’s Mount Vernon from ruin.

But developers have a way of getting what they want. Not even modernist architect Philip Johnson protesting in front of New York’s Penn Station was able to save the McKim, Mead & White masterpiece in 1963. Two years later, fearing that the world’s architectural treasures were being squandered, retired army colonel James Gray founded the International Fund for Monuments (now the World Monuments Fund). Without the WMF’s campaign in 1996, the deteriorating south side of Ellis Island, gateway for 12 million immigrants, might have been lost to history.

The fight never ends. I still miss the magnificent beaux-arts interior of the old Rizzoli Bookstore on 57th Street in Manhattan. The 109-year-old building was torn down in 2014. Nothing like it will ever be seen again.