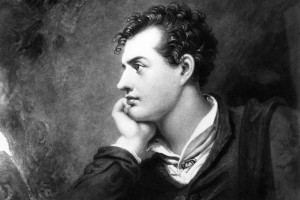

English Romantic poet George Gordon Noel Byron (from around 1810). To keep his weight down, he subsisted on a diet of flattened potatoes drenched in vinegar. PHOTO: HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

Resolutions and Jan. 1 have a fatal attraction for one another—much like beer and pizza. The vow most often cited, “to go on a diet,” also happens to be the one most quickly abandoned. According to a 2013 British study, two out of five dieters don’t make it beyond the first week.

The problem isn’t that people are lazy or spoiled. It’s that the purpose of a diet has become divorced from its original intentions. The ancient Greeks were largely responsible for the concept. “Diatia” means “way of life” or “regimen.” How a person approached the business of eating was as important as what entered his stomach. Balance, self-control and proper order were thought to be three key aspects to living the good life. Only barbarians, such as the Persians, gorged on luxuries.

The two greatest doctors of the classical world, Hippocrates (around 460 to 375 B.C.) and Galen (A.D. 129 to about 216) had strong ideas about the kind of diatia everyone should follow. They argued that the mind and body were controlled by four humors: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. The goal was to keep them in equilibrium. A surplus of phlegm, for example, could make a patient lethargic, requiring more citrus in the diet. Too much black bile, on the other hand, made a person melancholic—which, Galen thought, required bloodletting or purging to remove the noxious humors from the body.

Continue reading…