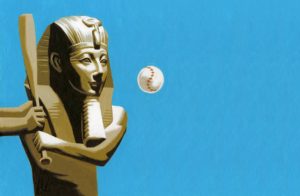

WSJ Historically Speaking: Baseball, From a Pharaoh to Hoboken, N.J.

PHOTO: THOMAS FUCHS

Say goodbye to the winter blues. On April 2 the sport of kings is set to resume: no, not horse racing but baseball, the oldest ball game on record.

At the dawn of civilization, our ancient ancestors learned how to write, build temples, sail the seas—and play ball. It will probably come as no surprise to baseball fans that the Egyptians placed the game (or their proto-variation of it) on a par with life and sex. According to Prof. Peter Piccione at Charleston College, the term “seker-hemat,” often translated as “batting the ball,” began as a fertility ritual performed in spring festivals. It’s believed that the ball represented the head of Osiris, god of the underworld.

Sacred wall paintings in Queen Hatshepsut’s temple near Luxor display some of the earliest references to the combined use of ball and stick. They show her stepson King Thutmose III (around 1479-1425 B.C.) ready to bat a ball at two priests. The inscription above Thutmose reads: “striking the ball for [the goddess] Hathor,” and the one above the priests: “It is the priest who catches it for him.”

The basic concept behind seker-hemat—a ball, a bat, a hitter, some catchers—endured even after its religious purpose was forgotten. Some 800 years ago, Asian-Turkish tribes may well have introduced a version to Romanian shepherds. Their game, “oina,” included not only batting but also hitting the players with the ball.

In medieval England, “stoolball,” where a stool was the pitcher’s target, soon became such a popular village sport that King Edward III (1312-1377) appears to have prohibited it on holidays because it was a distraction from useful archery practice. The Pilgrims at Plymouth did more than celebrate the first Thanksgiving in 1621: They also played the first game of American stoolball.

That game gradually gave way to cricket, in which two batsmen defend wickets of three wooden stumps, and rounders, which resembles softball, although the bat is short and held in one hand. When a soldier in George Washington’s army at Valley Forge recorded in his diary in April 1778 that he “playd at base” all afternoon, he may have meant rounders.

Most towns played their own versions— such as town ball, round ball and the “Massachusetts game”—and the differences led to arguments among teams. It wasn’t until a New York bank clerk named Alexander Cartwright created an official rule book based on “New York” rounders that baseball was born. In 1845 Cartwright formed the Knickerbocker club (named after the fire company where he volunteered) in the hope that a baseball league would follow. A year later, on June 19, 1846, at Elysian Fields in Hoboken, N.J., the Knickerbockers played the New York Nine in the first officially recorded baseball game.

By the end of the Civil War, New York-style baseball had become a national sport. One reason may have been its affinity with American political principles. Despite baseball’s ancient and noble heritage, it is a powerful expression of the democratic idea of e pluribus unum (out of many, one). When taking the field it’s a team effort, but when at bat it comes down to the individual. Even then, as Ernest L. Thayer’s poem “Casey at the Bat” memorably reminds us, any player who thinks he’s a king will, like mighty Casey, “in haughty grandeur there,” end up looking mighty foolish.