WSJ Historically Speaking: As You Dislike It: The Anti-Shakespeare Club

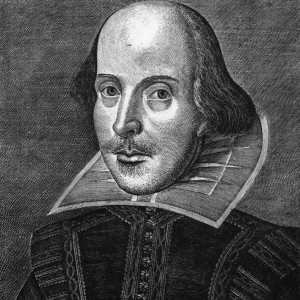

Why people still brush up on their Shakespeare. PHOTO: HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

In David Lodge’s 1975 novel “Changing Places,” a group of university professors play a party game called Humiliation, competing to see who has read the fewest great works of literature. A professor of English literature is in the lead, having declared his ignorance of Longfellow’s “Song of Hiawatha,” when Harold Ringbaum, a man with “a pathological urge to succeed,” declares that he’s never read “Hamlet.” The more he insists, the more the others scoff—until Ringbaum angrily swears a solemn oath to the fact, by which time everyone is stone cold sober with embarrassment.

Ringbaum’s faux pas neatly sums up Shakespeare’s towering presence in modern culture—underlined by the tempest of celebrations marking the 400th anniversary of the Bard’s death, which falls on Saturday. His reputation exists on a plane separate from other writers. With apologies to a speech from “Richard II,” Shakespeare himself has become a precious stone set in a silver sea of words.

Yet over the centuries, a surprising roster of famous writers and celebrated personages has picked quarrels with the Man from Stratford. Though complaints about the Bard have run the gamut from the moral to the artistic, one type is almost unique to him. I call it WAMS, or the What-About-Me Syndrome.

Among the first to suffer its ravages was Shakespeare’s friend, fellow dramatist and eventual British poet laureate . He seems never to have recovered from watching his Roman play “Sejanus His Fall” bomb while Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar” became an instant hit. Three years after the Bard’s death, Jonson could proclaim, “I loved the man and do honour his memory,” while simultaneously dismissing his work with the words, “Shakespeare wanted [that is, lacked] art.”

Two later poet laureates took it upon themselves to rescue Shakespeare from his alleged lack of artistry by writing new, improved versions of his plays. William Davenant decided that “Measure for Measure” worked much better when combined with “Much Ado About Nothing.” John Dryden, reworking “Troilus and Cressida,” said that someone had “to remove that heap of Rubbish, under which many excellent thoughts lay wholly bury’d.”

It was “King Lear”—with Lear’s madness, Gloucester’s blinding and Cordelia’s murder—that seemed to trouble Shakespeare’s early critics the most. To safeguard English sensibilities, yet another poet laureate, Nahum Tate, offered up his talents. He gave “King Lear” a happy ending, restoring Lear to mental health and marrying Cordelia off to Edgar.

Tate’s adaptation was such a crowd-pleaser that the original disappeared from the stage for more than 150 years. Americans remained wedded to happy “Lear” until Edwin Booth insisted on staging the original in 1875.

While some WAMS sufferers tried to save Shakespeare from himself, others questioned whether the Bard was worth saving at all. On Sept. 29, 1662, London diarist Samuel Pepys watched “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” “which I had never seen before, nor shall ever again, for it is the most insipid ridiculous play.” In true Pepysian style, he found solace in the dancing and “some handsome women.”

Voltaire (1694-1778), who didn’t share Pepys’s weakness for pretty faces, denounced “Hamlet” for being so absurd one might think it “the fruit of the imagination of a drunken savage.” Still, the French philosopher loved and hated Shakespeare equally, having translated his works into French (with the usual perverse meddling and “improvements”).

One of the most advanced cases of WAMS belonged to Leo Tolstoy. Rereading Shakespeare in old age, the Russian writer of “War and Peace” declared that the plays made him feel “repulsion, weariness and bewilderment.” In an essay published in English in 1906, Tolstoy insisted that anyone who praised “Lear” had to be delusional.

Four decades later, George Orwell wrote that Tolstoy was being “willfully blind” for reasons that had little to do with literature. Orwell couldn’t help speculating whether Tolstoy’s attack was merely projection. After all, he noted, the similarities between King Lear and the great Russian novelist are uncanny, from their renunciation of public life to their final flight into the countryside “accompanied only by a faithful daughter.”

Tolstoy wasn’t alone in suffering from a myopia induced by WAMS. President John Quincy Adams, an enemy of slavery, was nevertheless unmoved by Desdemona’s death “because her passion for [Othello] is unnatural; and why is it unnatural, but because of his color?”

Like Tolstoy, George Bernard Shaw took exception to Shakespeare’s lack of proper moral purpose, “his complete deficiency in that highest sphere of thought.” He took Shakespeare to task for being “an ordinary sort…a narrow-minded middle-class man”—an observation perfectly suited to the mind of a middle-class socialist such as Shaw.

With a similar lack of irony, Virginia Woolf complained that Shakespeare had a habit of throwing in a “volley” of words to disguise “when tension was slack,” while for T.S. Eliot it was an unaccountable emphasis on mothers that made “Hamlet” an “artistic failure.”

Since then, outright Shakespeare haters have largely faded from view, but WAMS still endures. The distinguished Shakespearean actor Ian McKellen surprised fans last year by telling them not to “bother” reading Shakespeare and just to see the plays staged.

Could the critics have been bullied into silence? That is certainly the view of the main character in Arthur Phillips’s 2011 novel “The Tragedy of Arthur,” who declares: “I have never much liked Shakespeare…I wonder if there isn’t a large and shy population of tasteful readers who secretly agree with me.” The current Broadway hit “Something Rotten” includes a song called “God, I Hate Shakespeare,” which takes aim at the “twits” who “prattle on about his great accomplishments.” Do audiences quietly agree that, as the song has it, “He’s a hack”?

If the Bard showed up to mark the anniversary of his death, it’s hard to say how he would answer his critics. Perhaps he would counsel modesty, reminding them that even the greatest writers are “such stuff as dreams are made of, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”