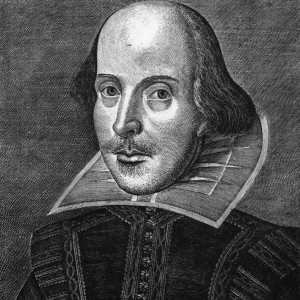

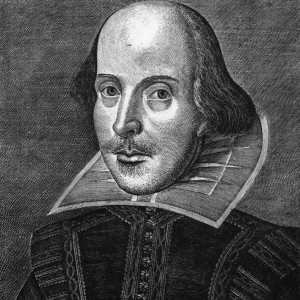

Why people still brush up on their Shakespeare. PHOTO: HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

In David Lodge’s 1975 novel “Changing Places,” a group of university professors play a party game called Humiliation, competing to see who has read the fewest great works of literature. A professor of English literature is in the lead, having declared his ignorance of Longfellow’s “Song of Hiawatha,” when Harold Ringbaum, a man with “a pathological urge to succeed,” declares that he’s never read “Hamlet.” The more he insists, the more the others scoff—until Ringbaum angrily swears a solemn oath to the fact, by which time everyone is stone cold sober with embarrassment.

Ringbaum’s faux pas neatly sums up Shakespeare’s towering presence in modern culture—underlined by the tempest of celebrations marking the 400th anniversary of the Bard’s death, which falls on Saturday. His reputation exists on a plane separate from other writers. With apologies to a speech from “Richard II,” Shakespeare himself has become a precious stone set in a silver sea of words.

Yet over the centuries, a surprising roster of famous writers and celebrated personages has picked quarrels with the Man from Stratford. Though complaints about the Bard have run the gamut from the moral to the artistic, one type is almost unique to him. I call it WAMS, or the What-About-Me Syndrome.

Among the first to suffer its ravages was Shakespeare’s friend, fellow dramatist and eventual British poet laureate Continue reading…