WSJ Historically Speaking: For Feb. 29, Tales of the Calendar Wars

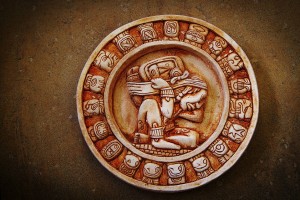

A carved Mayan calendar on textured background. Despite the provisional nature of calendars, two real phenomena govern almost all of them: the phases of the moon and the rotations of the sun. PHOTO: ISTOCK

Every four years on Feb. 29, we are reminded of one of life’s most puzzling conundrums: Time is both arbitrary and immutable. The “leap” making its appearance this Monday shows that the Western calendar on which we place so much reliance is a conceit—a piece of fiction introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in October 1582.

Despite the provisional nature of calendars, two real phenomena govern almost all of them: the phases of the moon and the rotations of the sun. Our Mesolithic ancestors were the first people to harness the movements of the cosmos to provide a fixed notion of the past, the present and the future. The oldest known calendar in the world was discovered in a Scottish field in 2013, notched into the earth some 10,000 years ago. Our forebears had created it by shaping 12 specially dug pits around a 164-foot arc to mimic the phases of the moon and track the months.

The design was sophisticated and yet simple enough that it could be modified easily. However, as with the lunar Islamic calendar today, the ancient Scots were constantly having to adjust for the differences between the lunar and solar calendars. To help with realignments, they tied their calibrations to a notch in the ground that marked the rising sun of the midwinter solstice.

Since a solar year is 365 days, five hours and about 49 minutes, every culture and civilization until the global adoption of the Gregorian calendar had to have a method for accommodating the leap days. In ancient times, the Babylonians would add a month at intervals of two and three years. The early Romans had a calendar of only 355 days, which led them to insert an extra month into late February every other year so that religious festivals wouldn’t occur out of season. After Julius Caesar’s reforms in 46 B.C., the Roman year had 12 months, 365 days and a leap year every four years. Even so, the calendar needed resetting every 131 years.

The Mayans made the most ingenious attempt at tackling the accuracy problem. They perfected a system using three corresponding calendars simultaneously. The last of them, the Long Count, measured the universe in life cycles of 7,885 solar years. (Much New Age quackery resulted from the belief that the end of the last cycle on Dec. 21, 2012, signified the end of the world.

Pope Gregory XIII’s calendar was able to prevent Christmas and Easter from creeping forward with a one-time leap forward of 10 days in October 1582. The calendar also used a more-accurate mathematical formula for leap years that excludes from the leap-year calendar any century years unless they’re exactly divisible by 400. But for all its brilliance, the new calendar couldn’t solve the problem that all of history before Oct. 15, 1582, became unmoored from its original dates.

Britain and its colonies stubbornly clung to the old Julian calendar until 1752, when they were also forced to change New Year’s Day from March 25 to Jan. 1.

Among those caught up in the calendar wars was George Washington. He was brought up believing he had been born on Feb. 11, 1731. But by the time he died in 1799, he had not only gained a different birthday but also grown a year younger; the New Year’s Day change had resulted in his birth date moving to Feb. 22, 1732.

Perhaps it’s just as well that his birthday is now celebrated on the uncertain date of the third Monday of every February.