Durable, stackable and skimmable, books have been the world’s favorite way to read for two millennia and counting.

August 3, 2023

A fragment of the world’s oldest book was discovered earlier this year. Dated to about 260 B.C., the 6-by-10-inch piece of papyrus survived thanks to ancient Egyptian embalmers who recycled it for cartonnage, a papier-mache-like material used in mummy caskets. The Graz Mummy Book, so-called because it resides in the library of Austria’s Graz University, is 400 years older than the previous record holder, a fragment of a Latin book from the 2nd century A.D.

Stitching on the papyrus shows that it was part of a book with pages rather than a scroll. Scrolls served well enough in the ancient world, when only priests and scribes used them, but as the literacy rate in the Roman Empire increased, so did the demand for a more convenient format. A durable, stackable, skimmable, stitched-leaf book made sense. Its resemblance to a block of wood inspired the Latin name caudex, “bark stem,” which evolved into codex, the word for an ancient manuscript. The 1st-century Roman poet and satirist Martial was an early adopter: A codex contained more pages than the average scroll, he told his readers, and could even be held in one hand!

Thomas Fuchs

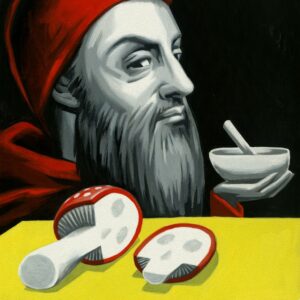

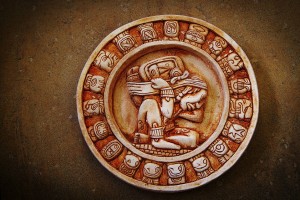

The book developed in different forms around the world. In India and parts of southeast Asia, dried palm-leaves were sewn together like venetian blinds. The Chinese employed a similar technique using bamboo or silk until the third century A.D., when hemp paper became a reliable alternative. In South America, the Mayans made their books from fig-tree bark, which was pliable enough to be folded into leaves. Only four codices escaped the mass destruction of Mayan culture by Franciscan missionaries in the 16th century.

Gutenberg’s printing press, perfected in 1454, made that kind of annihilation impossible in Europe. By the 16th century, more than nine million books had been printed. Authorities still tried their best to exert control, however. In 1538, England’s King Henry VIII prohibited the selling of “naughty printed books” by unlicensed booksellers.

Licensed or not, the profit margins for publishers were irresistible, especially after Jean Grolier, a 16th-century Treasurer-General of France, started the fashion for expensively decorated book covers made of leather. Bookselling became a cutthroat business. Shakespeare was an early victim of book-piracy: Shorthand stenographers would hide among the audience and surreptitiously record his plays so they could be printed and sold.

Beautiful leather-bound books never went out of fashion, but by the end of the 18th century, there was a new emphasis on cutting costs and shortening production time. Germany experimented with paperbacks in the 1840s, but these were downmarket prototypes that failed to catch on.

The paperback revolution was started in 1935 by the English publisher Allen Lane, who one day found himself stuck at a train station with nothing to read. Books were too rarefied and expensive, he decided. Facing down skeptics, Lane created Penguin and proceeded to publish 10 literary novels as paperbacks, including Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms.” A Penguin book had a distinctive look that signaled quality, yet it cost the same as a packet of cigarettes. The company sold a million paperbacks in its first year.

Radio was predicted to mean the downfall of books; so were television, the Internet and ebooks. For the record, Americans bought over 788.7 million physical books last year. Not bad for an invention well into its third millennium.