Building places for ordinary people to read and share books has been a passion project of knowledge-seekers since before Roman times.

July 8, 2021

“The libraries are closing forever, like tombs,” wrote the historian Ammianus Marcellinus in 378 A.D. The Goths had just defeated the Roman army in the Battle of Adrianople, marking what is generally thought to be the beginning of the end of Rome.

His words echoed in my head during the pandemic, when U.S. public libraries closed their doors one by one. By doing so they did more than just close off community spaces and free access to books: They dimmed one of the great lamps of civilization.

Kings and potentates had long held private libraries, but the first open-access version came about under the Ptolemies, the Macedonian rulers of Egypt from 305 to 30 B.C. The idea was the brainchild of Ptolemy I Soter, who inherited Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great, and the Athenian governor Demetrius Phalereus, who fled there following his ouster in 307 B.C. United by a shared passion for knowledge, they set out to build a place large enough to store a copy of every book in the world. The famed Library of Alexandria was the result.

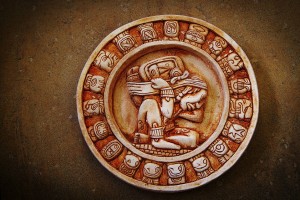

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

Popular myth holds that the library was accidentally destroyed when Julius Caesar’s army set fire to a nearby fleet of Egyptian boats in 48 B.C. In fact the library eroded through institutional neglect over many years. Caesar was himself responsible for introducing the notion of public libraries to Rome. These repositories became so integral to the Roman way of life that even the public baths had libraries.

Private libraries endured the Dark Ages better than public ones. The Al-Qarawiyyin Library and University in Fez, Morocco, founded in 859 by the great heiress and scholar Fatima al-Fihri, survives to this day. But the celebrated Abbasid library, Bayt al-Hikmah (House of Wisdom), in Baghdad, which served the entire Muslim world, did not. In 1258 the Mongols sacked the city, slaughtering its inhabitants and dumping hundreds of thousands of the library’s books into the Tigris River. The mass of ink reportedly turned the water black.

By the end of the 18th century, libraries could be found all over Europe and the Americas. But most weren’t places where the public could browse or borrow for free. Even Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Philadelphia, founded in 1731, required its members to subscribe.

The citizens of Peterborough, New Hampshire, started the first free public library in the U.S. in 1833, voting to tax themselves to pay for it, on the grounds that knowledge was a civic good. Many philanthropists, including George Peabody and John Jacob Astor, took up the cause of building free libraries.

But the greatest advocate of all was the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. Determined to help others achieve an education through free libraries—just as he had done as a boy —Carnegie financed the construction of some 2,509 of them, with 1,679 spread across the U.S. He built the first in his hometown of Dumferline, Scotland in 1883. Carved over the entrance were the words “Let There Be Light.” It’s a motto to keep in mind as U.S. public libraries start to reopen.