From ancient times until the Renaissance, beer-making was considered a female specialty

The Wall Street Journal, October 9, 2019

These days, every neighborhood bar celebrates Oktoberfest, but the original fall beer festival is the one in Munich, Germany—still the largest of its kind in the world. Oktoberfest was started in 1810 by the Bavarian royal family as a celebration of Crown Prince Ludwig’s marriage to Princess Therese von Sachsen-Hildburghausen. Nowadays, it lasts 16 days and attracts some 6 million tourists, who guzzle almost 2 million gallons of beer.

Yet these staggering numbers conceal the fact that, outside of the developing world, the beer industry is suffering. Beer sales in the U.S. last year accounted for 45.6% of the alcohol market, down from 48.2% in 2010. In Germany, per capita beer consumption has dropped by one-third since 1976. It is a sad decline for a drink that has played a central role in the history of civilization. Brewing beer, like baking bread, is considered by archaeologists to be one of the key markers in the development of agriculture and communal living.

In Sumer, the ancient empire in modern-day Iraq where the world’s first cities emerged in the 4th millennium BC, up to 40% of all grain production may have been devoted to beer. It was more than an intoxicating beverage; beer was nutritious and much safer to drink than ordinary water because it was boiled first. The oldest known beer recipe comes from a Sumerian hymn to Ninkasi, the goddess of beer, composed around 1800 BC. The fact that a female deity oversaw this most precious commodity reflects the importance of women in its production. Beer was brewed in the kitchen and was considered as fundamental a skill for women as cooking and needlework.

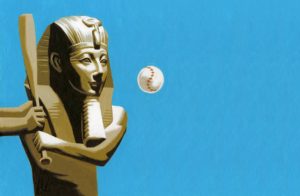

The ancient Egyptians similarly regarded beer as essential for survival: Construction workers for the pyramids were usually paid in beer rations. The Greeks and Romans were unusual in preferring wine; blessed with climates that aided viticulture, they looked down on beer-drinking as foreign and unmanly. (There’s no mention of beer in Homer.)

Northern Europeans adopted wine-growing from the Romans, but beer was their first love. The Vikings imagined Valhalla as a place where beer perpetually flowed. Still, beer production remained primarily the work of women. With most occupations in the Middle Ages restricted to members of male-only guilds, widows and spinsters could rely on ale-making to support themselves. Among her many talents as a writer, composer, mystic and natural scientist, the renowned 12th century Rhineland abbess Hildegard of Bingen was also an expert on the use of hops in beer.

The female domination of beer-making lasted in Europe until the 15th and 16th centuries, when the growth of the market economy helped to transform it into a profitable industry. As professional male brewers took over production and distribution, female brewers lost their respectability. By the 19th century, women were far more likely to be temperance campaigners than beer drinkers.

When Prohibition ended in the U.S. in 1933, brewers struggled to get beer into American homes. Their solution was an ad campaign selling beer to housewives—not to drink it but to cook with it. In recent years, beer ads have rarely bothered to address women at all, which may explain why only a quarter of U.S. beer drinkers are female.

As we’ve seen recently in the Kavanaugh hearings, a male-dominated beer-drinking culture can be unhealthy for everyone. Perhaps it’s time for brewers to forget “the king of beers”—Budweiser’s slogan—and seek their once and future queen.