‘WSJ Historically Speaking: Tis the Season to Stop Fighting

For some, a traditional Christmas means church and carols; for others, it means presents under the tree. But for countless millions, Christmas also means a day of epic family arguments. As the novelist Graham Greene once observed, “Christmas it seems to me is a necessary festival; we require a season when we can regret all the flaws in our human relationships: it is the feast of failure, sad but consoling.”

A recent survey conducted for the British hotel chain TraveLodge appears to support Greene’s gloomy contention. Two years ago, the chain noticed a sharp upswing in bookings for Christmas Day. Hoping to capitalize on the trend, its marketing department commissioned a poll of 2,500 households to see how the typical British family spends Christmas Day. The findings offered few useful insights for the company but proved a gold mine for sociologists.

The respondents revealed that, on average, the first fight of the day takes place no later than 10:13 a.m., usually after the discovery that someone has consumed all the chocolate. A lull then ensues while presents are opened and the drinks cabinet raided. At 11:42 or so, the children express their disappointment with their haul while the parents become enraged by their lack of gratitude. At noon comes a “discussion” of the level of alcohol consumption before lunch, followed by simmering tension until everyone finally sits down to eat around 2:23. The fragile truce established during the turkey carving is destroyed by a massive family row at 3:24. Exhaustion then sets in until 6:05, when tempers flare over the remote control. At 10:15, there is one final blowup before everyone goes to bed.

In short, the average family can expect at least five arguments between Santa’s midnight dash and the time Donner, Blitzen, Prancer and Vixen are back in their stables.

But one doesn’t have to read Charles Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol” to know that heartening lessons can be learned from Christmases past as well as present. For bickering families, perhaps the most useful of these is the reminder that anger may be righteous but forgiveness is divine. On Dec. 25, 1868, three years after the Civil War’s end, President Andrew Johnson defied his many critics to issue a final amnesty proclamation. The pardon brought every Confederate, repentant or otherwise, back into the national fold. Goodwill to all didn’t immediately follow. Echoing the words of the poet Robert Frost, the U.S. still had “promises to keep, and miles to go before I sleep.” But Lincoln’s vision of a reunited country with malice toward none could at last begin to take shape.

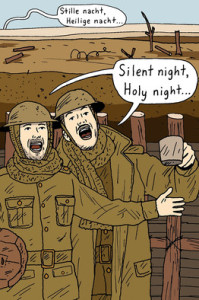

The second lesson—that peace is always possible, no matter the circumstances—comes from the Christmas Day Truce of 1914. It is the story of two regiments—one British, the other German—that celebrated Christmas during World War I by playing soccer in No Man’s Land. For the antagonists mired in the freezing mud of Ypres, their vision of Christmas yet-to-come was bleak indeed. Nevertheless, late on Christmas Eve, a German regiment gathered to sing “Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht.” British troops responded from their side by singing the English version, and soon the night air was filled with the rich harmony of the men’s voices. In the morning came a tentative wave, followed by an exchange of messages and then the first handshake. It was the British who produced the ball, and the Germans who won the match, 3-2.

Perhaps a way of avoiding the tantrums next Christmas is to remember the trenches and think silently, “God bless us, every one.”