The deadly affliction, once called self-starvation, has become much more common during the confinement of the pandemic.

February 18, 2022

Two years ago, when countries suspended the routines of daily life in an attempt to halt the spread of Covid-19, the mental health of children plunged precipitously.

Two years ago, when countries suspended the routines of daily life in an attempt to halt the spread of Covid-19, the mental health of children took a plunge. One worrying piece of evidence for this was an extraordinary spike in hospitalizations for anorexia and other eating disorders among adolescents, especially girls between the ages of 12 and 18, and not just in the U.S. but around the world. U.S. hospitalizations for eating disorders doubled between March and May 2020. England’s National Health Service recorded a 46% increase in eating disorder referrals by 2021 compared with 2019. Perth Children’s hospital in Australia saw a 104% increase in hospitalizations and in Canada, the rate tripled.

Anorexia nervosa has a higher death rate than any other mental illness. According to the National Eating Disorders Association, 75% of its sufferers are female. And while the affliction might seem relatively new, it has ancient antecedents.

As early as the sixth century B.C., adherents of Jainism in India regarded “santhara,” fasting to death, as a purifying religious ritual, particularly for men. Emperor Chandragupta, founder of the Mauryan dynasty, died in this way in 297 B.C. St. Jerome, who lived in the fourth and fifth centuries A.D., portrayed extreme asceticism as an expression of Christian piety. In 384, one of his disciples, a young Roman woman named Blaesilla, died of starvation. Perhaps because she fits the contemporary stereotype of the middle-class, female anorexic, Blaesilla rather than Chandragupta is commonly cited as the first known case.

The label given to spiritual and ascetic self-starvation is anorexia mirabilis, or “holy anorexia,” to differentiate it from the modern diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. There were two major outbreaks in history. The first began around 1300 and was concentrated among nuns and deeply religious women, some of whom were later elevated to sainthood. The second took off during the 19th century. So-called “fasting girls” or “miraculous maids” in Europe and America won acclaim for appearing to survive without food. Some were exposed as fakes; others, tragically, were allowed to waste away.

But, confusingly, there are other historical examples of anorexic-like behavior that didn’t involve religion or women. The first medical description of anorexia, written by Dr. Richard Morton in 1689, concerned two patients—an adolescent boy and a young woman—who simply wouldn’t eat. Unable to find a physical cause, Morton called the condition “nervous consumption.”

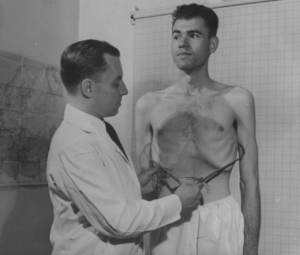

A subject under study in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, 1945. WALLACE KIRKLAND/THE LIFE PICTURE COLLECTION/SHUTTERSTOCK

Almost two centuries passed before French and English doctors accepted Morton’s suspicion that the malady had a psychological component. In 1873, Queen Victoria’s physician, Sir William Gull, coined the term “Anorexia Nervosa.”

Naming the disease was a huge step forward. But its treatment was guided by an ever-changing understanding of anorexia’s causes, which has spanned the gamut from the biological to the psychosexual, from bad parenting to societal misogyny.

The first breakthrough in anorexia treatment, however, came from an experiment involving men. The Minnesota Starvation Experiment, a World War II –era study on how to treat starving prisoners, found that the 36 male volunteers exhibited many of the same behaviors as anorexics, including food obsessions, excessive chewing, bingeing and purging. The study showed that the malnourished brain reacts in predictable ways regardless of race, class or gender.

Recent research now suggests that a genetic predisposition could count for as many as 60% of the risk factors behind the disease. If this knowledge leads to new specialized treatments, it will do so at a desperate time: At the start of the year, the Lancet medical journal called on governments to take action before mass anorexia cases become mass deaths. The lockdown is over. Now save the children.

A shorter version appeared in The Wall Street Journal