Honey has always been a sweet treat, but it has also long served as a preservative, medicine and salve.

February 9, 2023

The U.S. Department of Agriculture made medical history last month when it approved the first vaccine for honey bees. Hives will be inoculated against American Foulbrood, a highly contagious bacterial disease that kills bee larvae. Our buzzy friends need all the help they can get. In 2021, a national survey of U.S. beekeepers reported that 45.5% of managed colonies died during the preceding year. Since more than one-third of the foods we eat depend on insect pollinators, a bee-less world would drastically alter everyday life.

The loss of bees would also cost us honey, a foodstuff that throughout human history has been much more than a pleasant sugar-substitute. Energy-dense, nutritionally-rich wild honey, ideal for brain development, may have helped our earliest human ancestors along the path of evolution. The importance of honey foraging can be inferred from its frequent appearance in Paleolithic art. The Araña Caves of Valencia, Spain, are notable for a particularly evocative line drawing of a honey harvester dangling precariously while thrusting an arm into a beehive.

Honey is easily fermented, and there is evidence that the ancient Chinese were making a mixed fruit, rice and honey alcoholic beverage as early as 7000 BC. The Egyptians may have been the first to domesticate bees. A scene in the sun temple of Pharaoh Nyuserre Ini, built around 2400 B.C., depicts beekeepers blowing smoke into hives as they collect honey. They loved the taste, of course, but honey also played a fundamental role in Egyptian culture. It was used in religious rituals, as a preservative (for embalming) and, because of its anti-bacterial properties, as an ingredient in hundreds of concoctions from contraceptives to gastrointestinal medicines and salves for wounds.

The oldest known written reference to honey comes from a 4,000-year-old recipe for a skin ointment, noted on a cuneiform clay tablet found among the ruins of Nippur in the Iraqi desert.

The ancient Greeks judged honey like fine wine, rating its qualities by bouquet and region. The thyme-covered slopes of Mount Hymettus, near Athens, were thought to produce the best varieties, prompting sometimes violent competition between beekeepers. The Greeks also appreciated its preservative properties. In 323 B.C., the body of Alexander the Great was allegedly transported in a vat of honey to prevent it from spoiling.

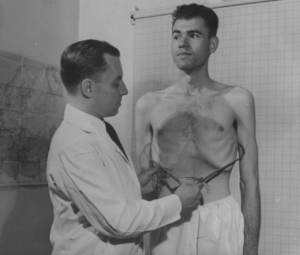

Honey’s many uses were also recognized in medieval Europe. In fact, in 1403 honey helped to save the life of 16 year-old Prince Henry, the future King Henry V of England. During the battle of Shrewsbury, an arrowhead became embedded in his cheekbone. The extraction process was long and painful, resulting in a gaping hole. Knowing the dangers of an open wound, the royal surgeon John Bradmore treated the cavity with a honey mixture that kept it safe from dirt and bacteria.

Despite Bradmore’s success, honey was relegated to folk remedy status until World War I. Then medical shortages encouraged Russian doctors to use honey in wound treatments. Honey was soon after upstaged by the discovery of penicillin in 1928, but today its time has come.

A 2021 study in the medical journal BMJ found honey to be a cheap and effective treatment for the symptoms of upper respiratory tract infections. Scientists are exploring its potential uses in fighting cancer, diabetes, asthma and cardiovascular disease.

To save ourselves, however, first we must save the bees.