Today’s debate over compulsory treatment for the mentally ill has roots in a history of good intentions gone awry

January 12, 2023

This year, California and New York City will roll out plans to force the homeless mentally ill to receive hospital treatment. The initiatives face fierce legal challenges despite their backers’ good intentions and promised extra funds.

Opposition to compulsory hospitalization has its roots in the historic maltreatment of mental patients. For centuries, the biggest problem regarding the care of the mentally ill was the lack of it. Until the 18th century, Britain was typical in having only one public insane asylum, Bethlehem Royal Hospital. The conditions were so notorious, even by contemporary standards, that the hospital’s nickname, Bedlam, became synonymous with violent anarchy.

Plate 8 of WIlliam Hogarth’s ‘A Rake’s Progress,’ titled ‘In The Madhouse,’ was painted around 1735 and depicted the hospital known as ‘Bedlam.’

PHOTO: HERITAGE IMAGES VIA GETTY IMAGES

The cost of treatment at Bedlam, which consisted of pacifying the patients through pain and terror, was offset by viewing fees. Anyone could pay to stare or laugh at the inmates, and thousands did. But social attitudes toward mental illness were changing. By the end of the 18th century, psychiatric reformers such as Benjamin Rush in America and Philippe Pinel in France had demonstrated the efficacy of more humane treatment.

In a burst of optimism, New York Hospital created a ward for the “curable” insane in 1792. The Quaker-run “Asylum for the Relief of Persons Deprived of the Use of Their Reason” in Pennsylvania became the first dedicated mental hospital in the U.S. in 1813. By the 1830s there were at least a dozen private mental hospitals in America.

The public authorities, however, were still shutting the mentally ill in prisons, as the social reformer Dorothea Dix was appalled to discover in 1841. Dix’s energetic campaigning bore fruit in New Jersey, which soon built its first public asylum. Designed by Thomas Kirkbride to provide state-of-the-art care amid pleasant surroundings, Trenton State Hospital served as a model for more than 70 purpose-built asylums that sprang up across the nation after Congress approved government funding for them in 1860.

Unfortunately, the philanthropic impetus driving the public mental hospital movement created as many problems as it solved. Abuse became rampant. It was so easy to have a person committed that in the 1870s, President Grover Cleveland, while still an aspiring politician, successfully silenced the mother of his illegitimate son by having her spirited away to an asylum.

In 1887, the journalist Nellie Bly went undercover as a patient in the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island), New York. She exposed both the brutal practices of that institution and the general lack of legal safeguards against unwarranted incarceration.

The social reformer Dorothea Dix advocated for public mental health care.

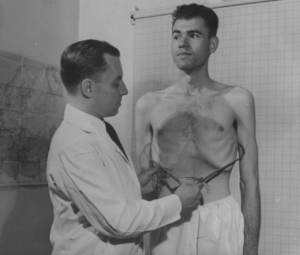

During the first half of the 20th century, the best-run public mental hospitals lived up to the ideals that had inspired them. But the worst seemed to confirm fears that patients on the receiving end of state benevolence lost all basic rights. At Trenton State Hospital between 1907 and 1930, the director Henry Cotton performed thousands of invasive surgeries in the mistaken belief that removing patients’ teeth or organs would cure their mental illnesses. He ended up killing almost a third of those he treated and leaving the rest damaged and disfigured. The public uproar was immense. And yet, just a decade later, some mental hospitals were performing lobotomies on patients with or without consent.

In 1975 the ACLU persuaded the Supreme Court that the mentally ill had the right to refuse hospitalization, making public mental-health care mostly voluntary. But while legal principles are black and white, mental illness comes in shades of gray: A half century later, up to a third of people living on the streets are estimated to be mentally ill. As victories go, the Supreme Court decision was also a tragedy.