All wars involve suffering and bloodshed, but not all defeats must lead to death or living hell. One reason why next week’s 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War invites national commemoration instead of civil unrest is that, from the outset, the chief Union protagonists consciously promoted the ideal of victorious restraint toward the vanquished South.

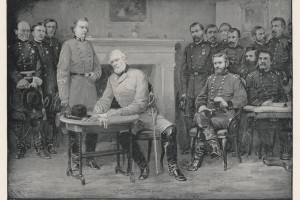

When Gen. Ulysses S. Grant met with Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee on April 9, 1865, the Union commander showed he understood that winning the peace would be as important as winning the war. His conditions for surrender included allowing Lee’s men to keep their sidearms for protection, as well as a horse or a mule for the spring harvest. For his part, Lee urged his men to accept their defeat with dignity and to return home for good.

In later years, for all the disappointments that followed during Reconstruction, Grant’s foresight at Appomattox remained a touchstone for peace and rapprochement, helping keep the spirit of unity alive.