WSJ Historically Speaking: Mercy in Victory Is as Ancient as War

All wars involve suffering and bloodshed, but not all defeats must lead to death or living hell. One reason why next week’s 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War invites national commemoration instead of civil unrest is that, from the outset, the chief Union protagonists consciously promoted the ideal of victorious restraint toward the vanquished South.

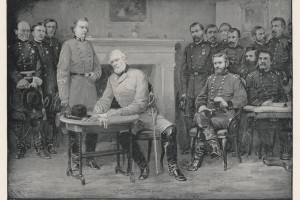

When Gen. Ulysses S. Grant met with Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee on April 9, 1865, the Union commander showed he understood that winning the peace would be as important as winning the war. His conditions for surrender included allowing Lee’s men to keep their sidearms for protection, as well as a horse or a mule for the spring harvest. For his part, Lee urged his men to accept their defeat with dignity and to return home for good.

In later years, for all the disappointments that followed during Reconstruction, Grant’s foresight at Appomattox remained a touchstone for peace and rapprochement, helping keep the spirit of unity alive.

Contrary to popular belief, our ancestors understood the moral and practical benefits of clemency as well as anyone today. The oldest complete law code in the world, the 18th-century B.C. Code of Hammurabi, was the fruit of war and conquest. After conquering all of southern Mesopotamia, the Babylonian Hammurabi self-consciously styled himself the “king of justice.” Instead of embarking on a mass slaughter of his defeated subjects, he set about uniting his empire under a single set of laws. A stele carved in 1754 B.C. (now in the Louvre) lists the code’s 282 laws and declares that Hammurabi was sent by Babylon’s patron deity, Marduk, to “rule over men” to bring about “the well-being of the oppressed.”

Magnanimity in victory is one thing; reconciliation is harder to achieve. But in one of history’s most striking acts of forbearance, the ancient Athenians rebuilt their shattered democracy in 403 B.C. by granting a general amnesty to all the parties responsible for the civil war that broke out after the Peloponnesian War. The amnesty spared Athens from what could have become an endless cycle of retaliation between those who backed its oligarchs and those who sought democracy. The governing council and all jurors were later required to take an annual oath: “We will remember past offenses no more.”

In the next millennium, when leaders often killed thousands in the name of religion, the surrender of Jerusalem in 638 to Umar ibn al-Khattab—the second of the four Rashidun (“rightly guided”) caliphs who led the Muslim community after the death of the ProphetMuhammad—stands out for its bloodless transition from Christian to Muslim rule. There was no massacre once Umar’s army took the city, nor was there a mass destruction of Christian shrines. Instead, the caliph allowed Christians to worship as before—albeit with a few provisos, including allowing Jerusalem’s original inhabitants, the Jews, to return and practice their religion too. Umar also had Judaism’s holiest site, the Temple Mount, restored and again made a place of worship, special to all three faiths.

In modern times, when the behavior of victors toward the defeated has ranged from the generous Marshall Plan instigated by the U.S. after World War II to the unmitigated horror of today’s self-styled Islamic State caliphate, history offers proof that mercy is no mere fluke in man’s nature.